Builder tactics under scrutiny

Long-used procedure of using ‘fill’ questioned in the post-Harvey era

By Mike Snyderand Nancy Sarnoff

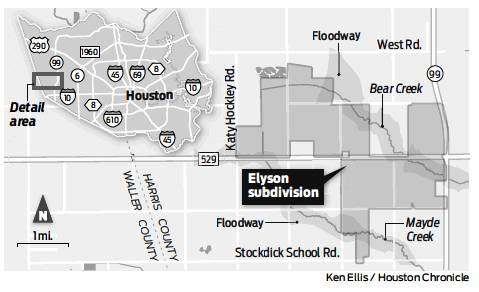

Newland Communities executives spent two years buying up Katy Prairie cattle pastures to assemble the 3,600-acre site of the company’s new master-planned community. They dubbed it Elyson — a tribute to Ely Freeman, one of the original settlers of the Katy area.

The location, adjacent to the Grand Parkway, was ideal. The fine public schools in Katy ISD would be a big draw for families. The topography, though, was a problem: Three flood plains crossed parts of the property.

Developers prefer to avoid the regulations involved in building in flood plains, and prospective buyers are leery of the risks and requirements to buy flood insurance. To overcome these obstacles, Newland turned to a well-established procedure: The company decided to raise homes above the flood plain with dirt, or fill, excavated from other areas of the site.

While the use of fill for this purpose is not uncommon in the Houston area, some experts say it’s questionable — particularly at a time when long-held assumptions about flood resilience are being re-examined in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey.

“The big problem in the Houston area is, you start using fill, you can fill so much that there’s no storage left,” said Larry Larson, director emeritus of the Association of State Floodplain Managers.

Harris County requires developers to offset fill by creating an equivalent amount of water storage, typically through on-site detention. Such rules reduce adverse impacts but don’t eliminate them, Larson said.

Jim Blackburn, a Houston lawyer and Rice University professor who has emerged as a leading voice in discussions about protecting the Houston region from catastrophic floods, said the use of fill to lift property out of flood plains is “legal, but arguably unethical. It sends the wrong message,” creating a perception of safety from flooding that may not be justified.

Ted Nelson, the president and chief operating officer for New-land Communities’ west region, said engineers hired by the company provided assurances that using fill to elevate lots, along with other steps to ensure good drainage, would provide a high level of flood protection.

“We had the ability to do this all within the site that we were considering purchasing,” Nelson said. “The soils there were good; we could use them for fill dirt. The system actually slows down the release of that floodwater into the Addicks Reservoir.”

Assured they were safe

Elyson is in an early stage of development. Nelson said the homes are being elevated 1 foot above the level of the 100-year flood plain, and the foundation slabs add another 12-15 inches.

In contrast, some of the homes in two neighborhoods in The Woodlands where fill was used were raised less than a foot above the flood plain level, according to Federal Emergency Management Agency documents. More than 300 homes flooded in these neighborhoods, Timarron and Timarron Lakes.

Owners who had been assured that their homes were safe from rising water now struggle to understand how to make good decisions when so many of the old rules no longer seem to apply, said Don Hickey, a bank executive whose home in Timarron Lakes flooded.

“I was somebody who was informed,” Hickey said. “Someone who is not informed doesn’t have a chance.”

When Hickey bought his home, he made sure it was more than 5 feet above the 100-year flood plain because he knew floods from nearby Spring Creek in 1994 had exceeded that level. Even so, Harvey’s rains put 7 inches of water into his house.

A post-Harvey analysis by Hickey and other residents concluded that most of the homes that flooded during the hurricane were built on land that was raised using fill.

As Newland Communities planned the Elyson development, the San Diego-based company in 2016 obtained so-called LOMR-F documents — letters of map revision based on fill — for more than 300 home lots in the first section of the northwest Harris County community. These documents empowered the company to tell buyers, accurately, that their homes were not in the 100-year flood plain, which is land deemed to have a 1 percent chance of flooding in a given year.

Lenders typically require buyers of homes in the 100-year flood plain to purchase federal flood insurance, which is optional outside the flood plain. Structures in the flood plain also can be subject to stricter building requirements.

Increasingly, though, the reliability of this standard as a measure of flood risk is being questioned. The Houston area has experienced three 500-year floods — events with a 0.2 percent chance of occurring in any given year — since 2015. And a recent Houston Chronicle analysis found that almost three-quarters of the 204,000 Harris County homes and apartment buildings damaged by Harvey were outside the 100-year flood plain.

“The 100-year flood plain is obsolete,” Blackburn said.

As development of Elyson continues, many, but not all, of its planned 6,200 houses will require fill, Nelson said. The use of LOMR-F documents, he said, “is a fairly common way of developing in many locations. It’s not new by any stretch of the imagination.”

Harris County processed 17 projects in 2017 that obtained LOMR-F letters, according to county flood control district spokeswoman Dimetra Hamilton.

Newer homes fared best

The concerns about the use of fill are part of a broader debate about what responsible development looks like in a post-Harvey era. It’s a contentious discussion, as shown by the City Council’s narrow 9-7 approval on Wednesday of stricter development rules proposed by Mayor Sylvester Turner.

Questions about where and how to build are particularly resonant for developers of large suburban projects such as Ely-son, which have big footprints that cover prairies and fields with hard surfaces that don’t absorb water.

Much of the recent discussion about these developments, particularly those in the flourishing market west of the city, has focused on their effect on flooding downstream. But flooding within the communities can be a problem as well.

People like to live near water, and the streams that course through many of the area’s most successful suburban developments are at once a marketing tool and a potential source of misery when torrential rains push them out of their banks. In Fort Bend County, for example, Harvey’s rains flooded hundreds of homes in master-planned communities along the Brazos River.

Overall, newer subdivisions fared better during Harvey.

Since Harris County updated its regulations governing new subdivisions in 2009, more than 75,000 single-family homes have been built in the county’s unincorporated areas. Of those, about 470 flooded during the hurricane.

“One of the safest places to be in Harvey was in a new house,” said Scott Davis, senior vice president of Meyers Research, a real estate consulting firm.

For developers eyeing new projects in flood plains, adding fill is one of several ways to obtain map revision letters from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Some Houston-area developments where this technique was used have fared well during recent major floods.

In Bridgeland, a master-planned community more than three times the size of Elyson that also obtained LOMR-F documents, not one house flooded from rising water during Harvey or the Tax Day Flood in 2016, said Heath Melton, vice president of master-planned communities for the Howard Hughes Corp., the developer of Bridge-land and The Woodlands.

Melton attributes that record in part to new guidelines enacted after Tropical Storm Allison. He cited the community’s detention, pipe sizes and other drainage systems.

When Harvey struck last August, close to 2,900 homes were occupied in Bridgeland, located east of the Grand Parkway and south of U.S. 290.

Elyson’s drainage system performed well during Harvey, according to a report by the engineering firm BGE Inc. The company reported in September that Harvey had flooded streets in the development, but no water entered any of the 94 houses occupied at that time. The risk of flooding could increase, however, as more structures are built on the property.

The site of the new master-planned community features clusters of finished houses dwarfed by vast stretches of empty land with home sites staked out. The eight homebuilding companies involved in the project have posted “lot available” signs around the property.

‘Buying the brand’

Jennifer Jones, whose family moved into its new house in Ely-son last year, said she and her husband researched the flood issues and understood that the land where her house stands had been in a flood plain until the builder elevated it with fill.

“Absolutely,” Jones said, when asked if she was confident these steps would protect her house from flooding. She said she was assured that no houses in Elyson flooded during Harvey, “arguably the worst flood that we’ve ever had.”

Nelson said it’s up to homebuilders to inform residents about flooding issues. Strictly speaking, he added, “there is no requirement to inform them because we’re not in a flood plain.”

Hickey, whose home in Timarron Lakes did flood, said he and his neighbors have learned to be skeptical of assurances from builders and developers.

“The Woodlands was built not to flood,” he said. “Everybody has this sense of, ‘Oh, this is The Woodlands. I’m buying the brand. I’m buying the protection.’ ” mike.snyder@chron.com nancy.sarnoff@chron.com