Travel alert worries border businesses

‘Misleading’ risk level for Mexican state will harm region’s image, official fears

By Olivia P. Tallet

Texas border business leaders are concerned that the U.S. Department of State’s recently escalated risk level for the Mexican state of Tamaulipas to “do not travel” status could discourage investment, scare off tourists and shackle the region’s economic growth.

The department recently changed its classification system of travel advisories to four levels of risk, and Tamaulipas was assigned the highest — the same rating assigned to countries such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

“That creates a problem for us because what (the department) is basically saying is that we are also a war zone, but we are not in a war zone,” said Keith Pat-ridge, president and CEO of the McAllen Economic Development Corporation, a public group dedicated to promoting business in the McAllen area and neighboring Reynosa across the border in Tamaulipas.

Companies operating on the border have long made adjustments to contend with the protracted drug war raging across the border, and so far the $92 million in annual exports of Texas goods to Mexico have not been interrupted.

In McAllen, where the local economy suffered a decline in 2017 as violent crimes increased across the border, business leaders are now concerned that the State Department’s “misleading classification” is going to create a reputation problem for the border region, Patridge said.

“It would be rippling throughout the economy … because it impacts the ability of companies to attract suppliers, to recruit employees to the area and so on,” he said.

Pablo Pinto, who directs the University of Houston’s Center for Public Policy, agrees the heightened risk assessment could damage a manufacturing sector that has blossomed as U.S. industries have located assembly plants south of the Rio Grande.

“Tamaulipas is home to maquiladoras (plants) and other industries that are strongly integrated into the North American economy,” Pinto said. “Here (in Texas) the short-run impact could be less important, but it may affect future investment and business decisions by American and even Mexican firms.”

The Reynosa factor

The State Department recently created a new system to assess the risk of traveling to foreign countries,and Mexico was assigned a Level 2 risk, with American travelers advised to “exercise increased caution.”

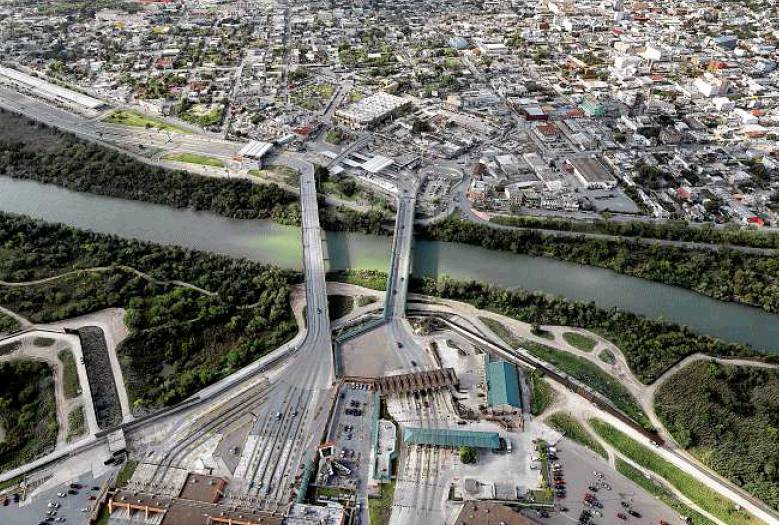

But risk levels were also assigned to individual Mexican states, and five, including Tamaulipas, were classified as having the highest risk. Tamaulipas comprises about a third of the 1,250 miles of the Texas-Mexico border, running along the Rio Grande from just upstream of Laredo, down to McAllen, Brownsville and to the Gulf of Mexico.

“Violent crime, such as murder, armed robbery, carjacking, kidnapping, extortion, and sexual assault, is common,” reads the new advisory on Tamaulipas.

The border state is home to the powerful Gulf Cartel, a crime syndicate that is engaged in a turf fight over control of key drug and human-smuggling routes, including with its breakaway enforcement arm known as Los Zetas.

Intentional homicides increased in Tamaulipas by 24.5 percent last year — to 804 from 615, according to statistics from Mexico’s National Security Commission. Other high-impact offenses, as Mexicans call those usually related to organized crime, also increased in the same period, with extortion and violent car robberies both rising by 40 percent.

Reynosa, the largest city on the Tamaulipas border and which sits across the river from McAllen, has been of particular concern for Mexican authorities as warring drug cartels often battle in broad daylight. The rate of intentional homicides was 28 percent, second in the state only to the capital of Victoria.

Francisco García Cabeza de Vaca, the governor of Tamaulipas, knows that stretch of the border area well. He was born and attended high school in McAllen, and he holds dual U.S. and Mexican citizenship. He was mayor of Reynosa from 2005-2007.

A member of Mexico’s leading opposition party, the conservative National Action Party, or PAN, Garcia has attributed the violent troubles in his state to the legacy of collusion between trafficking organizations and previous governors from the ruling party that controlled Tamaulipas for more than 80 years.

García took a strong stand against organized crime during his campaign, and his staff points to improvements they say he has made to public security in the sprawling state. Still, crime has escalated.

“We recognize that there is a problem,” spokesperson Aldo Hernández said. But, he adds, “the state has taken strong measures” during the past months that “we think will have an impact in this battle.”

Hernández mentioned the creation of a state highway police force in September to patrol key highway corridors, a response to roving bands of criminals who hold up buses, trucks and private cars. The state also launched a new police special forces unit in November, trained as SWAT teams and equipped with armored trucks, with a concentration on operations in Reynosa.

“We are going head-on, we are going against the enemies of peace in Tamaulipas,” García said during a ceremony announcing the units’ allocation. “There will be no truce against the violent; we will restore peace, order and the rule of law.”

Peaceful McAllen

Crime has not spilled over, however, onto the Texas side of the Tamaulipas border, said Wolfram Schaffler González, director of Texas A&M International University’s Texas Center for Border Economic and Enterprise Development.

“In fact, the (Texas) southern border counties have the lowest crime in the state,” he said.

Violence in Tamaulipas has taken a toll, however, on business conditions in McAllen as visitors eschew the city in favor of Laredo, said Steve Ahlenius, president of the McAllen Chamber of Commerce.

“The violence in Reynosa is having an economic impact in the sense that it’s stopping or redirecting Mexican nationals that travel from the Tamaulipas and Monterrey market to McAllen,” he said.

Businesses on the Texas side of the border have experienced decreases in revenues, particularly in the hospitality and restaurant industries that rely on visitors from Mexico for shopping and cross-border commercial trips.

After years of continuous economic growth, the economy of the McAllen metropolitan area declined in 2017 and “has been in a state of general stagnation” over the previous year, according to the McAllen Economic Index report. The number of border crossings also dropped during the year.

Other Texas cities bordering with Tamaulipas, like Laredo and Brownsville, didn’t have the same economic downturn. But crime in their neighboring Mexican cities of Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros wasn’t nearly as high as in Reynosa.

Tarnished reputation

For McAllen, reputation is vital to its economic prosperity, experts say.

“In today’s day and age, the stakes are higher than ever for cities to attract and grow businesses, which means that cities need to manage their reputational risk just as companies and public figures do,” said Jeff Berkowitz, CEO of Delve, a firm that specialize in issues management.

“The classification absolutely has a negative effect for employers on both sides of the border,” said Aaron Holt, a Houston employment lawyer with the international law firm of Cozen O’Connor.

Holt said that border cities on both sides have thrived by capitalizing on an attractive dynamic for investors: the lower cost of labor on the Mexican side and the geographic proximity to the large consumer base in the United States.

“If safety can’t be maintained, then the allure of profits is quickly offset by the risk and liability associated with security causing these companies to simply choose another, more stable area for their investments,” he said.

Meantime, border business owners are caught between spiking violence in neighboring Mexico and a publicity problem sparked by the State Department travel warning.

And with an economy that has thrived under the North American Free Trade Agreement, now under attack by President Donald Trump and his administration, the crossfire is only mounting for border cities.

“We have to move forward,” Ahlenius said. “And you kind of hope and pray for the best.” olivia.tallet@chron.com twitter.com/oliviaptallet