DEVELOPING STORM

Nature ruled, man reacted. Harvey was Houston’s reckoning.

The trillion gallons of water Hurricane Harvey dropped on Harris County in August revealed the downside of Houston’s dynamic economy. And the Corps of Engineers suddenly was faced with an awful choice.

ADDICKS PROJECT OFFICE, U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS KATY SUNDAY AUG. 27, 11:45 P.M. 49 HOURS, 45 MINUTES AFTER HARVEY’S LANDFALL

By Susan Carroll

Inside a squat, brick building at the base of Barker reservoir, Richard Long tossed and turned in his cot near midnight.

Dread and adrenaline kept him from drifting off.

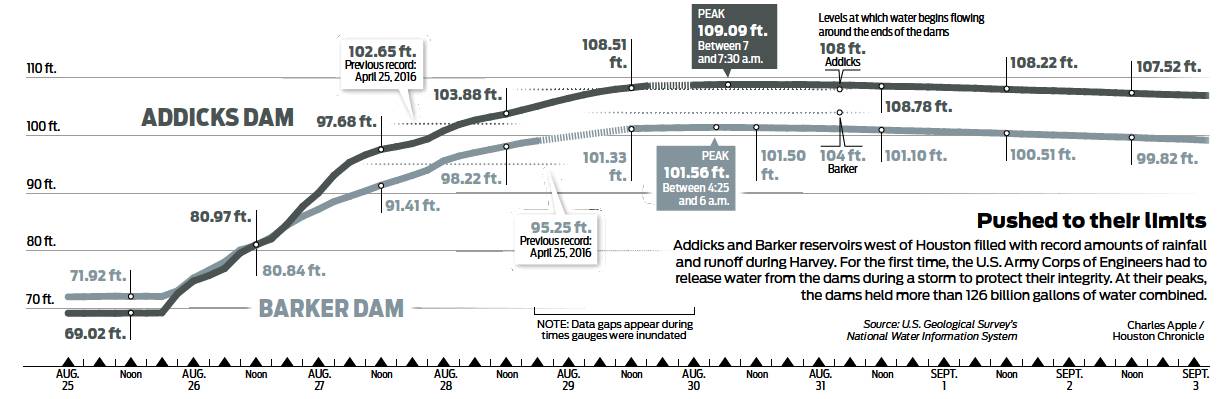

Water levels at the Ad-dicks and Barker dams west of Houston, the city’s primary defense during a major storm, were rising faster than he’d seen in his 38 years with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Addicks had climbed 28 feet since Hurricane Harvey made landfall along the central Texas coast on Aug. 25, two days earlier. Barker had risen 22 feet. Both dams likely would break their record pool levels within 24 hours.

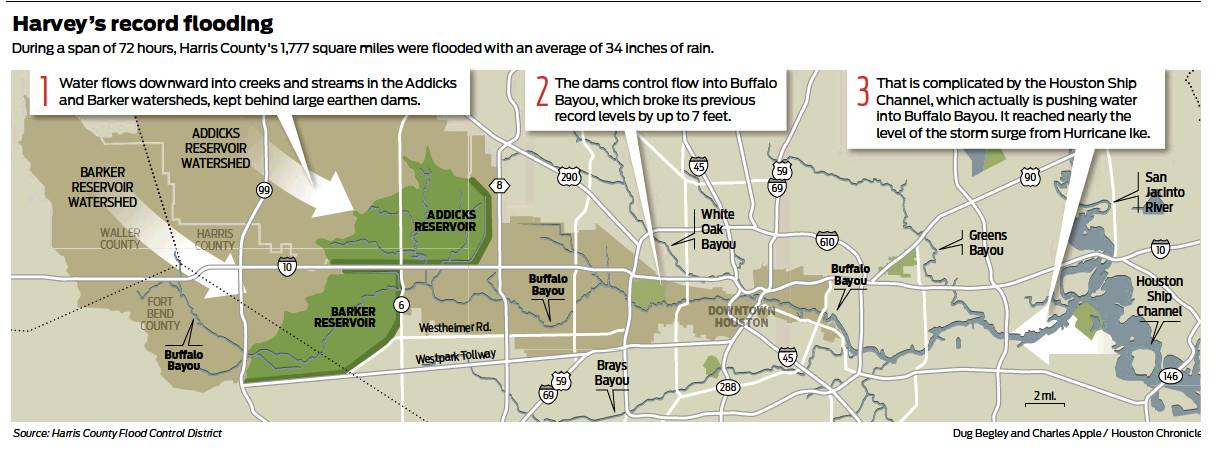

After decades of successfully taming Buffalo Bayou by impounding storm runoff inside the reservoirs until the skies cleared, the Corps had finally faced its Sophie’s Choice with Harvey: release water during a monster storm and doom houses along the bayou, or risk letting the water flow out from around the ends of the dams and over the emergency spillways — perhaps triggering a much bigger disaster.

Uncontrolled flows would risk erosion and failure of the earthen berms, potentially sending a catastrophic wall of water into the heart of the nation’s fourth-largest city. If the dams failed, thousands could die.

The Corps had announced that releases would start at 2 a.m. at Addicks — two hours away. But the reservoirs were rising faster than engineers had predicted.

And even with the releases, the Corps’ models showed the reservoir pool would climb so high that water would flow around the north end of Ad-dicks for the first time in the dam’s 70 years of operation.

The releases also wouldn’t spare homes built within the footprint of the reservoirs as the water level climbed toward the spillway. Many of those homes were doomed, too, Long knew.

Rain thrashed the roof.

Long’s mind raced from the dams to his wife, who was with his 89-year-old father at their home in Fulshear, 20 miles away, watching the water rise in the streets.

Suddenly, the dam’s captain, Chuck Ciliske, appeared at Long’s door. The parking lot was flooding. The Corps’ own building would be next.

“Richard,” he said, “We’ve got to go.”

Between midnight and 1 a.m., after Long and Ciliske abandoned the office, two groups of Corps employees climbed onto metal platforms that hold the control panels for the flood gates. Standing in the unrelenting rain, they opened the gates, the platforms vibrating as they sent murky stormwater downstream and into the already raging bayou.

BBB

The trillion gallons of water that Harvey dumped on Harris County during four days in August — enough to fill the Astrodome more than 3,300 times — revealed the downside of Houston’s dynamic economy. The region’s growth formula, which relies heavily on abundant, cheap housing and lax regulation, suddenly had a death toll in the dozens and a price tag in the billions.

Houston’s deference to developers was evidenced by the thousands of homes built in known flood plains and flood-ways, clogging the path of rushing floodwater and causing it to rise. Developers not only had built out to the bases of the reservoirs that once sat on the far western flank of Harris County, but inside them — within their flood pools — and right up to their emergency spillways. Over time, Houstonians became desensitized to the risks of living about 50 feet above sea level.

Prompted by a national flood insurance program that encouraged them to build in vulnerable areas, residents built closer and closer to the bayou that carries floodwater away from the reservoirs and out to the Gulf of Mexico.

The county’s extensive network of drainage channels —enough to stretch from Los Angeles to New York — could not keep up with the average of 34 inches that fell within four days. Some portions of southeast Texas recorded 60 inches of rain.

The National Weather Service had to add two more shades of purple to its maps to show how much water had fallen from the sky.

Before Harvey, proposals for major infrastructure projects, such as a third reservoir and dam and a dike for Galveston Bay, had gained little traction in Congress because of their multibillion-dollar price tags. The condition of Addicks and Barker had deteriorated so much that they were on the list of the country’s most dangerous dams.

All of this left local leaders to contend not only with the most rainfall in U.S. history, but with the consequences of decades of political inertia.

Interviews and records obtained by the Houston Chronicle show that, within a span of 72 hours, officials faced one agonizing decision after another as each inch of Harvey’s rain increased the flooding and spread the misery.

Harvey was Houston’s reckoning. Nature ruled. Man reacted.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

SATURDAY, AUG. 26, 6 A.M.

8 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Jeff Lindner sank into one of the 98 chairs on the floor of the windowless emergency operations center, a cavernous building near Interstate 10 and the 610 West loop.

Lindner, meteorologist for the Harris County Flood Control District, had watched Harvey intensify on the radar over a span of 40 hours from an ordinary tropical depression into a Category 4 hurricane — the first to strike the Texas coast since Ike in 2008.

Harvey’s eye made landfall at 10 p.m. the night before on San Jose Island, northeast of Corpus Christi. Winds peaked at 130 mph, and the storm surge reached 12 feet.

Most hurricanes typically move inland, away from the coast. But Harvey was predicted to stall over southeast Texas for days.

The National Weather Service was forecasting rainfall totals for Harris County of 20 to 30 inches, with isolated totals of 35 inches or more.

Lindner, 35, knew Harvey’s forecast was unprecedented. He’d done his best in TV appearances to explain what to expect. But how do you explain what 30 inches of rain looks like?

Lindner checked the county’s rainfall gauges. More than 2 inches had fallen within an hour near his house close to Addicks reservoir.

He was grateful that his wife, Lillie, and two children, ages 3 and 5, had left for Smithville, up near Austin, the day before.

He needed to focus.

ADDICKS PROJECT OFFICE

KATY

SATURDAY, AUG. 26, 8 P.M.

22 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Long, 61, had started working for the Corps of Engineers in the 1970s, back when development upstream of the reservoirs had just started and they were largely surrounded by pastures and rice fields.

For years, he’d warned that every inch of concrete poured upstream of the reservoirs made flooding into Addicks and Barker worse.

Long sent emails internally opposing the construction of the Grand Parkway upstream from Addicks in 2011, warning of negative impacts from more development upstream.

“Additional impervious surfaces within the Addicks and Barker watershed will increase the volume of flows into the reservoirs, the rate at which flows get to the reservoirs, and the size of the pool generated within the reservoirs,” he warned. It was built anyway, and more subdivisions sprouted near it.

Flood control officials said they had worked with Harris County commissioners to strengthen flood mitigation requirements upstream of the reservoirs last spring. But there were already thousands of homes inside the reservoirs, in the spillways and near Buffalo Bayou, which runs through Houston’s energy corridor and downtown before dumping into Galveston Bay.

The city blamed the county. The county blamed the city. Everybody blamed Congress.

Long was planning to retire once the Corps finished a $75million construction project to replace the aging outlets on the dams, which discharge stormwater through gates into the bayou.

The old outlets, still in use, had been reinforced and grouted since the Corps found voids and seepage beneath them in 2009. But those were temporary fixes: The Corps had ranked Addicks and Barker among the six most dangerous dams in its inventory of more than 700, calling them “extremely high risk.”

For years, Corps officials have requested $3 million for a study that would re-evaluate the future of the reservoirs in light of all of the development around them and address lingering safety concerns.

Harris County flood control officials had agreed to pay for half the cost, planning to examine what could happen if water went over the emergency spillway or around the ends of the dams. They also had proposed studying the impacts of higher rates of release from the dams on neighborhoods downstream.

The Corps and the county never got those answers. The study was not funded.

On his computer monitor, Long watched the reservoirs rise. He’d been amazed in 2016 by how fast they’d climbed during the Tax Day storm, which set records for pools for both dams.

Addicks had reached 102.65 feet, its flood pool within a foot of the height where it would have reached neighborhoods built in the reservoir. Barker topped out at 95.24, roughly 2 feet away from the level at which it would have reached homes.

At their peak, the reservoirs held a record 68 billion gallons of water — enough to fill the Astrodome 222 times.

Long thought he’d retire without seeing another storm like that. But it was clear from the gauges that Tax Day had nothing on Harvey.

Addicks was up to 86 feet.

The gauge at Barker had broken.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

SATURDAY, AUG. 26, 8:15 P.M.

22 HOURS, 15 MINUTES

AFTER LANDFALL

Lindner and National Weather Service meteorologists traded messages in a chat room.

“Plan is to issue a Flash Flood Emergency to include parts of S and SW Houston in Harris County and parts of E Fort Bend County,” a weather service meteorologist wrote.

“I agree,” Lindner wrote.

Brays Bayou is rising rapidly, Lindner warned three minutes later. The bayou runs from south of Barker Reservoir east through neighborhoods that include Meyerland and Braeswood Place.

“Jeff,” the NWS meteorologist replied, “going out with warning on Brays.”

The southeast side of the city, stretching down to Galveston Bay, was getting pounded. Gauges in Friendswood southeast of Houston showed 6.6 inches of rain in an hour. South Houston had 5 inches in a hour. Stretches of Interstate 10 flooded. Parts of downtown were underwater.

“Life threatening conditions developing,” Lindner tweeted. “Stay at your location.”

In a metro area of 6.6 million people, hundreds of thousands were threatened by flooding.

Harris County Judge Ed Emmett, 68, took to the lectern in the operations center for a hasty news conference at 10:40 p.m.

Emmett, the top elected official in the county, had suffered a mild stroke two weeks earlier and temporarily lost his vision. He was hospitalized and then released, his vision restored, and told to take it easy. Emmett had followed doctor’s orders, mostly, until Harvey hit.

The mayor and police chief barely made it in time; they had to abandon their vehicles near Old Katy Road and wade into the emergency operations center on foot. Behind them, the storm radar swirled on a big screen. Harvey was living up to the dire predictions.

Emmett spoke to a cluster of reporters and to his audience on Facebook live. “This,” he said, “is what we’ve been worried about.”

GREENSPOINT,

NORTH HOUSTON

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, 1 A.M.

27 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Police Chief Art Acevedo, who stands 6 feet tall, waded through waist-high water in Greenspoint around 1 a.m. in his uniform, helping evacuate two apartment complexes that had flooded near Greens Bayou.

“Stay in twosffl” Acevedo yelled.

“You got the baby?” he yelled.

Yes, someone yelled in the darkness.

Acevedo had mobilized all his officers on Friday night as Harvey approached. He waited in the rain on a Houston Fire Department boat, his uniform soggy from the downpour and fetid bayou water. Officers instead commandeered two buses from the airport and loaded the evacuees.

Thousands of people called 9-1-1, panicking.

Water reached the ceilings of some single-story homes along Interstate 45 and in southeast Houston. 9-1-1 overloaded.

Some callers got no answer. Others were put on hold as they watched the floodwater rise.

Acevedo arrived at the operations center in the darkness, prepared to order all of his officers to start working 24-hour shifts until further notice.

As he peeled off his uniform shirt, cockroaches jumped off him and scurried across the floor.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

SUNDAY AUG. 27, 4 A.M.

30 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Bob Royall and Rodney Reed, assistant chiefs with the Harris County Fire Marshal’s Office, took calls from local fire departments from their seats near Lindner in the emergency center. They’d assembled a database of more than 40 boats and dozens of high-water vehicles owned by local fire departments, not including Houston’s.

A man was clinging to the Texas 225 bridge in rushing floodwater.

Royall called the U.S. Coast Guard. The helicopter pilot couldn’t reach the man but spotted a pregnant woman and child who had climbed up on a roof. The crew flew them to safety.

Royall and Reed enlisted constables with airboats to reach stranded ambulances.

At daybreak, Royall stood next to Harris County Emergency Management Director Mark Sloan and stared at a big-screen TV with the radar of the storm. Another band of rain swirled over the city.

His phone buzzed with requests from local fire departments begging for boats and rescue vehicles.

He had none left. It was the emptiest feeling of his life.

He picked up his cellphone and texted his wife and two grown sons.

When you wake up in the morning, he typed, I want you to understand this has been the worst night of my career.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, 11 A.M.

37 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Reed, 35, ducked into the emergency center library, feeling helpless. He bumped into Gray Stansell with Harris County Risk Management.

“We might as well call in civilians,” Reed grumbled to Stan-sell.

“You should tell the judge,” Stansell replied.

“Tell the judge what?” asked Emmett, who had just walked into the library.

Reed turned around and saw Emmett, who had slept only two hours the night before. Frustrated with the Red Cross, the judge had spent the last day trying to get shelters open, and he was taking heat from the media about not calling for an evacuation.

“To where?” he had asked. No one knew where the rain was going to be the heaviest.

His youngest daughter, son-in-law and grandchildren had evacuated on an airboat from their Braes Heights neighborhood, where floodwater had reached some roofs and the middle of stop signs.

Gov. Greg Abbott had assured Emmett that morning that trucks and boats were ready to help. But they were just outside of the county, and the roads were impassable.

“Can we put a call out to citizens?” Reed asked Emmett.

“Well,” Emmett replied, “what’s your plan?”

Reed said they’d have volunteer rescuers call the emergency center. The operators would write down names, where the volunteers were, what kind of rescue equipment they had. They’d make sure they had life vests and then send them to the nearest fire department staging spot. That way, instead of people out there doing their own thing, there would be some order to it, he said.

“That’s a good idea,” the judge said. “You’d better hurry up, because I’m going downstairs and I’m going to brief the media.”

CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF

LATTER-DAY SAINTS

VICKSBURG, MISS.

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, 11:45 A.M.

37 HOURS, 45 MINUTES AFTER

LANDFALL

Roughly 400 miles northeast of the heart of the storm, Aaron Byrd’s phone vibrated during Sunday school at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Vicksburg, close to the Mississippi River. Byrd, a 40-year-old civil research engineer in the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, glanced down and saw it was an email from the lab’s director, who was on assignment to the Corps’ Operations Center.

Oh no, he thought.

The Addicks and Barker dams are among the most critical dams in the Corps’ inventory, the email read. We need information on them now.

Byrd helped develop an inundation modeling technology that can forecast flood depths up to five days in advance.

The Corps’ technology collects data on the water levels on the ground, topography, forecast rainfall and other factors. Then a supercomputer calculates millions of math equations that produce maps showing the flow of water.

The Corps had used it during hurricanes Irene in 2011 and Sandy in 2012. That Friday, Byrd and his team had used it to monitor Harvey as it hit the Texas coast.

At that point, the forecast included in the Corps’ bulletin on Addicks and Barker was relatively unremarkable: 10 to 15 inches of rain. No overtopping was expected, the bulletin said.

But Harvey had defied that forecast.

Byrd stood up in Sunday school and walked to the door, heading for the lab.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, NOON

38 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Emmett stood at the lectern in the press room, his glasses on the tip of his nose.

The county had deployed “every available rescue asset,” he said. People were still stranded and needed help. State resources couldn’t get in because of the flooding.

“We can’t wait for assets to come from the outside,” he said. “So those of you who have boats and high-water vehicles that can be used in neighborhoods to help move people out of harm’s way: We need your help.”

Lindner, the meteorologist, followed Emmett at the lectern, looking solemn in a white button-down shirt.

“We’re facing a catastrophe that we haven’t faced before. This is unprecedented, like the judge said,” Lindner said. “Every single watershed, all 22 of our watersheds, are over banks.”

The rain was starting to let up a bit, but Lindner and the Corps were closely watching the water levels in Addicks and Barker, which were still climbing.

To the northeast, near the San Jacinto River, neighborhoods in Kingwood and Humble were flooding. The San Jacinto River Authority was releasing 39,600 cubic feet per second from the Lake Conroe Dam, a record.

Greenspoint, in north Houston, had flooded so badly that people waded through neck-deep water.

Lindner’s home had flooded when he lived there in 2001 during Tropical Storm Allison. He kept thinking about it, how helpless he felt as the water poured in, and he panicked, lifting things to counters, seeing what he could save.

“I know what you’re going through,” Lindner said during the news conference. “I know you’re scared. I know you’re panicked. I know you feel a desperation right now. But know that help is coming.”

U.S. ARMY ENGINEER RESEARCH

AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER

VICKSBURG, MISS.

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, 8 P.M.

46 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Byrd, the civil research engineer in the Corps’ lab, pulled together data on the dams.

How did they work? What kind of condition were they in? Where was the water going to spill, if it went around the edges of the dams?

When Addicks and Barker were built in the 1940s, the original plans called for three reservoirs, not two, and a levee on Cypress Creek north of Addicks. A system of canals was supposed to carry water from Addicks and Barker to Galveston Bay.

But the discharge canals were shelved because rapid development made the land too costly. Since the 1940s, Houston’s population swelled from about 385,000 to more than 6.6 million, including its surrounding suburbs.

The levee was never built.

As originally designed, four of the dams’ five outlets had no gates. That allowed for a combined, uncontrolled discharge into Buffalo Bayou of 15,700 cubic feet per second. As the land near the bayou developed, people complained of damage from the discharges. By the 1960s, all of the outlets had gates to allow for controlled releases from the dams.

Now, with heavier development, it is allowed to release only 2,000 cubic feet per second combined from the two dams, as measured by a gauge in Buffalo Bayou at Piney Point, 10 miles downstream from Barker. In order to exceed 2,000 cfs, the dam operator needs permission from Corps officials in Dallas. Some streets and homes downstream of the reservoirs flood when the combined release rate from the reservoirs exceeds approximately 4,000 cubic feet per second, flood control records show.

That means the dams are holding more water than originally intended, and for longer.

Their design is unusual, Byrd noted, in that they don’t tie into hills. Each is miles long and shaped like a V. So once the depression fills up, the dams are vulnerable to “flanking flows” — water going around the ends.

Byrd’s job was to answer one question: where would all the water go once it hit the ground?

Byrd ate bacon cheddar potato chips from the vending machine for dinner at his desk, marveling at Harvey’s rainfall totals and the forecast, which called for more rain.

I-45 NEAR DOWNTOWN

HOUSTON

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, 9:51 PM

47 HOURS, 51 MINUTES AFTER

LANDFALL

Police Chief Acevedo rode in the passenger seat of a Hummer, heading north on deserted Interstate 45, past flooded cars, and into downtown, trying to reach police headquarters. It was Day 2 of heavy rain. Police were still having trouble reaching some people who needed to be rescued, but hundreds of volunteers with boats had made a huge difference. “Now the dams are about to open,” he said. “That’s not music to my ears.”

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

SUNDAY, AUG. 27, 11:59 P.M.

50 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

The water levels in the reservoirs climbed faster than the Corps had anticipated when it announced plans to start releases at 2 a.m. at Addicks and 11 a.m. at Barker. Seconds before midnight, a Corps hydraulic engineer sent an email to local officials and Corps employees: “We are beginning releases on both reservoirs right now.” The releases would start at 800 cubic feet per second from each reservoir, for a combined 718,000 gallons per minute, the Corps official wrote. During the next 10 hours, the goal was to increase that to 8,000 cubic feet per second, or 3.5 million gallons a minute. Francisco Sanchez, the county’s emergency management public information officer, awoke on his cot in the emergency center to pounding on the door. A voice resounded in the hallway: “The water is going outffl”

U.S. ARMY ENGINEER RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER

VICKSBURG, MISS.

MONDAY, AUG. 28, 9 A.M.

59 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Byrd had a model running that took into account the flooding already occurring, the rainfall, the releases and the forecast. The flooding would not just be “one home here, one home there,” he saw. “It was going to be miles and miles of homes.” The Corps asked Byrd to run a second model. People had built homes inside the reservoirs, he was told. Some of them would start flooding within hours, once the flood pool reached 103.4 feet in Addicks. At 9 a.m., it was at 103.37. Addicks is built to hold water up to 108 feet above sea level before it flows around the north end of the dam; above 111.5, the water would top the emergency spillway. The math is simple. Some of the homes would be nearly 8 feet underwater if the reservoir level reached the spillway. Barker had the same problem. The emergency spillway was at 105.1 feet. The lowest homes were 97.1 feet. The Corps wanted to know which homes were going to flood, and where, to get the information to first responders. Byrd pulled up Google Earth. He felt like falling out of his chair. He called another researcher over to his computer. It showed row after row of homes in the flood pools, thousands of them. Byrd scanned the area near Addicks’ spillway. There was a commercial center and sprawling subdivisions with two-story homes at the bottom of the spillway. “How did they get permission to build there?”

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

MONDAY, AUG. 28, 1:59 P.M.

64 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Edmond Russo with the Corps took to the lectern, reading from a prepared statement. Water behind both dams had reached record levels, he said. Addicks was at 104.36 feet. Barker had reached 98.59 feet. Homes in both flood pools started taking on water. The discharge rates for Ad-dicks reached 2,600 cubic feet per second. Barker reached 2,100 cfs. The Corps was trying to ramp the releases up, he said. “We would prefer not to let the water build up in the dam and go over the spillways because at that point we will not have control over the water,” Russo said. Buffalo Bayou was holding steady, Lindner said at the news conference. The releases were not expected to result in a rise in the bayou — not at the current rates. But it had already reached record levels, and it wasn’t dropping. Lindner studied the models of Addicks and the map of the spillway. If the pool hit 109.5 feet, the Corps had warned that the uncontrolled releases around the north end of Addicks would become stronger and spread faster and farther. He and his wife knew when they bought a house in a neighborhood near the Addicks spillway that this was possible. He just didn’t think it would ever really happen. Lindner called his wife, Lillie, in Smithville. “We might get water in the house,” he said. He heard her catch her breath.

BELTWAY 8 AT HARDY TOLL ROAD

NORTHEAST HOUSTON

MONDAY, AUG. 28, 11 P.M.

73 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Acevedo, the police chief, stared at the floodwater below the overpass at Hardy Toll Road and Beltway 8, still 16.5 feet deep. Detectives had traced Sgt. Steve Perez’s vehicle here but couldn’t be sure he was below. His wife had reported the 34-year veteran missing after he left home around 4 a.m. Sunday in the pouring rain. He never made it to his command post. Acevedo wanted to send in a dive team, he said, but he feared it was too dangerous because it was already dark. He couldn’t justify risking lives for what he knew would be a recovery mission, not a rescue. Acevedo said a prayer for Perez’s family and his soul. He left the car underwater until daybreak.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

TUESDAY, AUG. 29, 8 A.M.

82 HOURS AFTER LANDFALL

Addicks had reached 108.1 feet. It was full. Water started flowing around the north end of the dam, at the rate of a few thousand gallons per minute. The drainage system outside the reservoir, near the intersection of Brittmore Park and Tanner Road, had been able to absorb much of it. It was starting to threaten two subdivisions, Twin Lakes on Eldridge and Lakes on Eldridge. Barker had reached 101.5 feet. Some homes in the reservoirs had 5feet of water in them. Discharges had reached 7,300 cubic feet per second, Russo said, up from 4,700 the previous afternoon.

HARRIS COUNTY EMERGENCY

OPERATIONS CENTER

HOUSTON

TUESDAY AUG. 29, 7:59 P.M.

94 HOURS AFTER HARVEY’S

LANDFALL

Russo read from another prepared statement: Addicks had reached 108.9 feet. Barker was at 101.46. “Earlier today, we had to make the decision to make more aggressive releases than what we told the public before in order to maintain the functionality of our structures,” Russo said. “We understand the frustration this has caused for many people and pray for the safety and well being of those who have been impacted.” The current discharge rate, Russo said, was a combined 13,000 cubic feet per second. The goal was to reach 16,000 cubic feet per second, he said. Flooding along Buffalo Bayou was increasing, Lindner said at the news conference. The gauge at Dairy Ashford showed it had risen 1 foot and was expected to rise another 1.5 feet that night. Flood control officials had seen it from a helicopter earlier that day, Lindner said. There was “massive inundation never before seen in that portion of the bayou watershed.” A third of Harris County — an area the size of Austin — was underwater.

Epilogue Addicks climbed to 109.09 feet, just 0.41 inches from reaching the benchmark the Corps feared involving potential for heavier flows around the end of the dam, before starting to drop on Aug. 30. Barker also peaked that day, reaching 101.56 feet. Flooding along Buffalo Bayou continued for days. Mayor Sylvester Turner issued evacuation orders for homes and apartments with standing water in them along the energy corridor south of Addicks and east of Barker, citing the Corps’ releases from the dams. Lindner’s home in a neighborhood near the spillway did not flood. Gray Stansell’s home in Bellaire did flood. Sgt. Perez was laid to rest at a funeral attended by thousands. Releases from the Lake Conroe dam peaked at more than 79,000 cubic feet per second. The Corps announced the reservoirs were empty on Oct. 17. It is being sued by more than 1,000 plaintiffs in state and federal court.

Coming Sunday: Part 2 Decades of failed reforms.susan.carroll@chron.com twitter.com/susancarroll