Homeowners say drainage fix ignored

Flooded residents in The Woodlands fault utility district

By James Drew

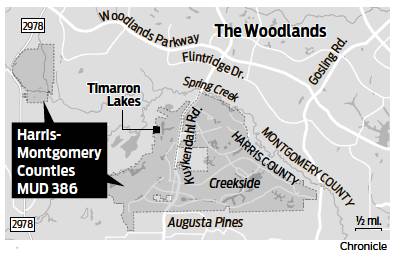

Homeowners in The Woodlands’ neighborhood called Timarron Lakes believe the flooding of 100 homes during Hurricane Harvey in August was most likely caused by a faulty drainage system that they had asked officials to overhaul after flooding in May 2016.

They helped organize a community meeting last week attended by 50 residents and are preparing to gather signatures on a petition stating their grievances. It’s addressed to an obscure local government entity called the Harris-Montgomery Counties Municipal Utility District 386, which sends them and thousands of other Woodlands homeowners property tax bills for drainage, water and sewer services.

Frank Gore, a 68-year-old retired businessman who plans to sign the petition, can’t hide his frustration, saying there’s a “circular loop” between The Woodlands Land Development Co., which developed the neighborhood and created MUD 386 to finance the water, sewer and drainage infrastructure, and the MUD itself, which says it inherited a drainage system designed by the developer’s engineers.

Hurricane Harvey is raising new questions about the role played by MUDs in flooded neighborhoods, their close ties to developers, and their accountability and transparency in dealing with the homeowners whose properties have been damaged or destroyed.

Howard Cohen, a partner with the Houston law firm that represents MUD 386, Schwartz, Page & Harding, said he knew of no evidence showing the drainage system had ever malfunctioned and that nothing could have prevented the flooding from Harvey. Tim Welbes, president of The Woodlands Land Development Co., a division of The Howard Hughes Corp., noted that Harvey caused flooding that was 36.8 percent greater than the flooding in 2016.

Identifying the problem

It was during the 2016 flood that Gore said he witnessed something that he found puzzling: While Spring Creek, behind his home, did not flood the neighborhood, water began rushing out of the storm drains into the street in front of his house and stopped within a few inches of his home. Six homes were flooded in Timarron Lakes and Timarron, the neighborhood next door. Gore and seven of his neighbors in the upscale development began investigating what had happened.

They ultimately concluded that the storm drains in Timarron Lakes had been inundated by water from Timarron, where Spring Creek had overflowed its banks. Timarron Lakes’ storm drains had filled with water, Gore and his neighbors discovered, because a 10-foot-deep drainage ravine that had previously allowed water to flow back into the creek had been filled in during the neighborhood’s development.

Earlier this year, months before Harvey, Gore and his neighbors asked the MUD to build a culvert where the ravine had been so that in a future flood, the water flowing into Timarron Lakes from Timarron could drain back into Spring Creek. But the MUD determined such a culvert would not make much of a difference.

After record rainfall during Harvey, Gore said, the neighborhood, once again, was inundated by water from the creek overflowing in Timarron, which had no way to drain away in Timarron Lakes. All told, 200 houses flooded in Timarron, and 100 flooded in Timarron Lakes, neighbors estimate.

“You’re kind of incensed at first, and then you go back, and say, ‘Folks, this is what we told you was going to happen,’ ” Gore said. “It’s going to happen again if they don’t do anything.”

MUDs have powered the explosive development of Greater Houston. They have vast authority to sell tax-exempt bonds on behalf of developers to finance roads and parks and drainage, water and sewer systems, and then to levy property taxes on homeowners, who repay those bonds over 25 years, with interest.

There are about 950 MUDs across Texas, but as a mechanism for developing formerly rural lands, they are most concentrated in the Houston area, with about 620 MUDs in Harris, Fort Bend and Montgomery counties alone. The Woodlands is located in Harris and Montgomery counties and is served by numerous MUDs.

Developers say MUDs have enabled growth and have helped keep housing prices low in Texas. But some taxpayers’ advocates contend they are beholden to the developers who create them, not accountable to homeowners and at least partially responsible for higher property taxes.

MUD 386 was created in 2001 by the state Legislature at the request of The Woodlands Land Development Co., which was represented at the time by Schwartz, Page & Harding. The firm later stopped representing the developer and became the MUD’s general counsel and bond counsel. Voters in 2005 officially approved the MUD as a government entity with taxing powers. The voters also officially elected the “temporary” board members picked by the developer.

Asking for a fix

These “elections” often involve a tiny number of voters paid by developers to temporarily reside on the land to be developed, often in trailers. Records show that two people voted in 2005 to authorize creation of MUD 386 with authority to sell up to $282 million in tax-exempt bonds. The MUD also has authority to sell an additional $293 million to refinance them. A resident doing research on the MUD recently showed the Houston Chronicle a picture of what he said was the mobile home where “rent-a-voters” lived temporarily on land to be developed so that they could vote.

MUD 386 initially covered 200 acres. But like a city, it has annexed land in The Woodlands since its creation and now spans 3,500 acres. The district has an estimated population of 17,006 and serves about 4,900 homes in some of the planned community’s newest neighborhoods. To date, it has sold $157 million in bonds, through multiple sales, since its creation to reimburse the developer for its infrastructure costs. The district is scheduled to sell $10.8 million in November for more developer reimbursements and for water, sewer and drainage projects so that 510 acres can be developed.

After the floods in 2016, Gore began corresponding with MUD 386, concerned the obvious drainage problems could get worse in future floods. He and other homeowners wanted the MUD to build the culvert to channel water that overflowed from Spring Creek in Timarron back into the creek without threatening their homes.

In an email on Jan. 26, 2017, Gore asked Chad Abram, senior vice president of the MUD’s engineering firm, Houston-based IDS Engineering Group, for a cost estimate for the culvert proposal. Gore wrote that he had spoken with Rich Jakovac, president of the MUD’s board of directors, who “stated that the project appeared to be too costly for the MUD to take on without outside assistance.”

In a Feb. 10 email to Gore with a copy to Jakovac, Abram wrote that the MUD board had approved spending $150,000 to regrade swales — land shaped with low spots between several houses to help floodwaters drain. He added that the board had tabled the two projects requested by residents — the culvert and a project to halt water in drainage pipes from backing up into Timarron Lakes.

“The District’s existing drainage improvements are designed to accommodate 100-year storm events as required by Harris County. These potential drainage improvements would only engage during an event greater than a 100-year storm, which is beyond the District’s current design standard,” according to a statement from Abram’s firm, IDS Engineering Group, which Abram attached to his email to Gore.

‘No benefit at any cost’

In a Feb. 13 email, Gore replied that “we have seen at least two events in the past 32 years that significantly exceeded the 100-year criteria.”

The following day, Abram told Gore in an email that the district initially thought a culvert “would be of benefit, but upon further review” concluded it would not carry enough water to Spring Creek. “Effectively no benefit at any cost,” he wrote.

Abram never gave him a cost estimate for the culvert, Gore said. Abram didn’t return messages seeking comment.

But Gore said in a recent interview that the culvert would have helped water inundating Timarron Lakes from Timarron drain back into Spring Creek.

“The culvert would have helped us a lot during Hurricane Harvey,” said Gore. “I don’t know if it would have solved the Hurricane Harvey problem, but it certainly would have mitigated it to a large extent.”

Cohen, the lawyer representing MUD 386, said the MUD’s board “is and has been actively engaged with its residents, consultants and other governing bodies (such as The Woodlands Township) in evaluating these flood occurrences and is working with those persons and bodies on possible District and regional solutions and funding to better address flooding within the area.”

Asked if development of the area had altered the drainage system, Welbes, president of The Woodlands Land Development Co., replied in an interview: “In the development and platting process, there are regulatory requirements, and we certainly have met all of those standards.”

He referred other questions to the MUD. Jakovac, president of the MUD’s board, didn’t return messages seeking comment.

Bernie Otten, 57, said he and his wife, Jeannie, moved into their home in December 2013 — his third house in The Woodlands over the past 24 years. He said his house, built on top of fill material, is above the 100-year flood plain and about 300 to 400 yards from the creek.

During Harvey, the creek sent four inches of water into his home — from the front and back.

Otten said the role of the developer and the MUD should be examined.

From 2012 through 2015, the district sold $85 million in tax-exempt bonds. Part of those proceeds were used to reimburse the developer for water, sewer and drainage projects in 30 sections of Creekside Park West, where Timarron Lakes and Timarron are located.

Each bond prospectus listed the district’s engineers as IDS Engineering Group and LJA Engineering.

“The engineers have also been employed by the Developer in connection with certain planning activities and the design of certain streets and related improvements within the district,” the documents state.

Otten, a former oil company manager, said he wanted to know whether the engineers who designed the drainage system were working for both MUD 386 and the developer.

Cohen, the attorney representing MUD 386, said he is “unable to answer engineering-related questions.” The Chronicle requested comment from the developer, The Woodlands Land Development Co., but did not receive a response.

‘Make residents whole’

Mike Giovinazzo, a 65-year-old businessman who lives in Timarron Lakes, said he believes MUD board members are trying to help residents affected by the flooding and have indicated “they can engineer, it but it will cost money.” He said the developer should pay for changes to the drainage system.

Gore agreed that he and other homeowners who pay property taxes to MUD 386 shouldn’t have to pay the bill for what he said was a drainage system that didn’t work.

Gore, who moved into his home in 2014 with his wife Valerie, said he wants The Woodlands Land Development Co. to “make residents whole” by improving the drainage system. He said the developer now is referring questions from residents to the MUD.

“We paid a premium for these lots,” Gore said. “I could have gone and built my house in Spring for a lot less money than in The Woodlands. We believe in The Woodlands brand and the cache that they do things right, and if they didn’t get it right, they will do it again, because that’s the way The Woodlands always has treated drainage and other things.”

Asked if The Woodlands Land Development Co. would pay for drainage changes requested by residents, Welbes said: “It’s a hypothetical, and we’ll have to wait and see what comes.”

MUD supporters often say that water districts are heavily regulated by the state, specifically the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which approves requests from MUDs to sell bonds.

But Brian McGovern, a TCEQ spokesman, said the state agency has “no jurisdiction to compel a water district or developer to improve or make changes to a drainage system.” james.drew@chron.com twitter.com/jamesjdrew

›› Learn about the risk that was hiding in plain sight in one west-side subdivision at

HoustonChronicle.com/ CanyonGate