Landmark Sears store to make way for something new

Retailer’s departure will boost Midtown, real estate experts say

By Katherine Blunt and Nancy Sarnoff

The landmark Sears store in Midtown will close after one last holiday season, marking another step in the long decline of yesterday’s department store and creating an opportunity for Houston developers to modernize a long sought-after property.

The building at 4201 Main will go dark in late January following a liquidation sale starting Nov. 10. The closure will herald the start of an expansive redevelopment project in a fast-growing area between downtown and the Texas Medical Center.

The decision to close the store culminates a deal between Sears and Rice Management Co., which is responsible for Rice University’s endowment. The company, which owns the six-acre parcel surrounding the building, in 1945 leased that land to Sears for 99 years.

Last week, Rice Management bought out the remaining 28 years of Sears’ lease and acquired about three adjoining acres owned by the retailer. Rice now owns 9.4 contiguous acres, including the original department store, its parking lots and the former Sears Automotive Center on Eagle Street between Fannin and San Jacinto. The acreage also includes the land under the Fiesta Mart, which Rice leases to the grocer at 4200 San Jacinto. Fiesta has two more years left on its lease.

Rice plans to initiate a yearlong study to determine redevelopment options with input from city officials, the Urban Land Institute, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research and other groups.

The Urban Land Institute, which often produces reports on notable properties and developments across the region, has not yet been tasked with working with the university on the Sears property. But David Kim, executive director of the organization’s Houston chapter, said he would welcome the opportunity to discuss it.

“I think location speaks for itself,” he said. “It’s in a densely populated area of the city.”

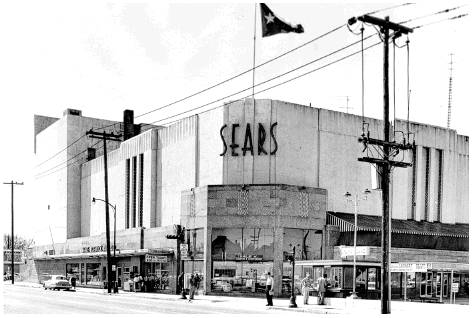

The Sears building, topped with a decades-old nameplate, is the company’s most recognizable Houston store, a monument to an era when department stores were the preferred means of retail catharsis.

The store opened in 1939 as a modern, air-conditioned shopping mecca, the first in the city where all the floors were connected by escalator. Sears employed an in-house muralist to paint the walls with scenes depicting decades of Texas history, including a large painting of Sam Houston lining the stairwell.

Much has changed since then. Sears shrouded the original facade with corrugated metal in an attempt to modernize the building in the 1960s, and many of the original murals have been covered.

Shoppers went elsewhere

The building, once an extension of the city’s shopping district, now sits in the middle of an area frequented by vagrants and panhandlers. But the company kept it open even as shoppers migrated elsewhere and began buying goods online.

The decision to give up the store aligns with a strategy Sears has pursued for years in an effort to cut costs and downsize its operations amid a seismic shift in the retail industry. The company, more than a century old, closed about 180 stores this year, including ones in Westwood and Bay-brook Mall.

By the end of the third quarter, it expects to shutter 150 more.

“This is not an effort solely aimed at cost savings,” spokesman Howard Riefs said in a statement. “Many of our larger stores are too big for our needs.”

Saddled with more than $3.5 billion debt, the company sold its Craftsman tool brand to Stanley Black & Decker in March for about $900 million. It recently began selling its Kenmore brand on Amazon in an acknowledgement of the e-commerce giant’s growing strength.

Other department-store chains have been forced to cut costs and experiment with new retail models amid an explosion in online sales and shopper demands for more personalized in-store experiences. Major players including Macy’s and J.C. Penney are in the process of closing hundreds of stores while investing more heavily in their e-commerce operations and revamping their remaining locations.

Sears faces some of the steepest challenges in the department-store sector as shopping preferences change and e-commerce sales climb. The company has for years reported the sharpest declines in foot traffic among many of its competitors, according to a recent report by Moody’s Investors Service.

Earlier this year, the company acknowledged “substantial doubt” about its ability to survive. It has reiterated its faith in its turnaround plan, but the admission raised questions among industry experts and shoppers about the company’s long-term viability.

Rice seizes the moment

Ed Wulfe, CEO and founder of commercial real estate firm Wulfe & Co., applauded Rice’s efforts to buy out the retailer’s lease as Sears continues to cut its store chain and re-evaluate its operations. The acquisition, he said, gives Rice control over a redevelopment opportunity that developers have considered for years.

“The timing was good for Sears and great for Rice, and Rice seized the moment,” he said. “This is the best possible thing that could have happened to the property.”

Rice’s portfolio of high-profile Houston properties also includes the Rice Village shopping center. That center was managed by Weingarten Realty Investors until 2014, when Rice bought out Weingarten’s ground lease for a figure estimated at between $55 million and $60 million.

Andrew Kaldis, an independent Houston developer whose has restored and repurposed historic properties throughout the urban core, wondered about the viability of saving the old Sears building. In 2012, he and a partner bought a 1930s commercial building just north of the store.

They restored it, added artist studios and sold it last year. He said whatever is redeveloped on the Rice property will be a shot in the arm for the surrounding area.

“We always thought that was the key to really spur that end of Midtown,” he said of the Sears.

Burdette Huffman, principal of Edge Realty Capital Markets in Houston, studied the property when getting his MBA at Rice. The Sears property was the subject of a prominent case study in a master’s class that combined business and architecture.

He agreed its redevelopment could be a catalyst for Midtown’s continued growth. The case study offered several possibilities for the site, he said, including residential, office and retail components in an area with access to light rail.

“It’s really a central hub between two major development and employment centers,” he said.

David Bush, executive director of Preservation Houston, sees the building as a prime opportunity to create a mixed-use development that incorporates some of the building’s midcentury architecture. He said his organization could help secure state and federal tax credits to preserve some of the original structure.

“Underneath all the aluminum siding is a really good art deco-style building,” he said. katherine.blunt@chron.com nancy.sarnoff@chron.com