Commentary

One road to efficient transportation may be paved with hydrogen

CHRIS TOMLINSON

In the race to replace oil as a transportation fuel, researchers at Rice University are giving hydrogen a boost by introducing an economical and ecological way of generating the gas.

Their breakthrough could make hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, which emit only water, competitive with electric vehicles that rely on batteries. While U.S. companies have focused on storing electricity in batteries, the Japanese government has promoted a hydrogen-based economy.

Both technologies aim to solve the same problem of how to store energy produced by renewable sources, such as wind and solar power, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The technology that comes to dominate this global competition will make or break entire industries.

Hydrogen is the most common element in the universe, but on Earth most of it is molecularly tied to something else, like carbon in natural gas or oxygen in water. To use hydrogen as a fuel, we have to break the hydrogen molecules free and isolate them.

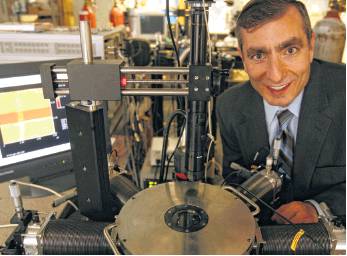

Jim Tour and his team of chemists and material scientists at Rice University have been working on finding a way to do this conveniently and inexpensively.

“How do you store electricity? You have to make it into a fuel — something you can put into a bottle and ship around,” Tour said. “Hydrogen is a great way to store electricity.”

The cheapest and most common way to produce hydrogen is to use heat, steam and a nickel catalyst to split methane into hydrogen and carbon dioxide. But generating one carbon dioxide molecule for every two hydrogen molecules makes little environmental sense if the goal is to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Chemists can produce hydrogen using other processes and catalysts, but they required enormous energy and were uneconomical. Until now.

Tour has been working with a form of carbon called graphene, which is a one-atom thick lattice that is stable, nontoxic, very light and very conductive. In 2014, Tour perfected a way to use a laser to grow graphene inexpensively on plastic, wood and other materials.

This month, Tour announced that his laser-induced graphene sheets, when coated with inexpensive nickel- or cobalt-based catalysts, can split two water molecules into two molecules of hydrogen and one molecule of oxygen. If the small amount of electricity needed for this process comes from wind or solar source, it produces no greenhouse gases.

“From one side of the graphene on plastic sheet comes hydrogen, and from the other comes oxygen, so you don’t have to do a gas separation, which normally you’d have to do,” Tour told me. “What these catalysts do is allow you to do it at a very low voltage, which is very efficient.”

Tour’s work was peer-reviewed in the American Chemical Society’s journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

A low-cost, highly efficient method of generating hydrogen improves the economic competitiveness of hydrogen fuel cells, which capture the energy produced when hydrogen and oxygen are combined to make water. Fuel cells can generate energy for as long as there is hydrogen and oxygen, which is usually taken from the atmosphere.

While U.S. automakers have focused on electric vehicles powered by lithium ion batteries, which store electricity as chemical energy, Japanese automakers have made major strides in reducing the cost of fuel cell cars. Toyota executives say they are working to develop a hydrogen infrastructure for Japan within 15 years.

“Fuel cell vehicles have been made. Tanks to store hydrogen to 5,000 pounds per square inch have been made,” Tour said. “With a battery, you are storing the electricity in the vehicle. Here you would store the electricity in the form of hydrogen, and you would bring it back in a fuel cell. The efficiencies would be very similar. But the amount of energy you can store is much, much greater in the hydrogen form.”

Fuel cell demonstration vehicles from Toyota, Hyundai, Honda and Mercedes-Benz have clocked more than 3 million miles and 27,000 refueling stops. They typically have a 250-mile range, like all-electric battery cars, but they can be refueled in five minutes compared to hours for recharging a battery. For now fuel cells are far more expensive than internal combustion engines or battery-powered cars.

Fuel cells, though, have many applications outside of transportation. Fuel cells are used for electricity generation in remote locations, including on spacecraft.

Japanese manufacturers are experimenting with home units that use solar power during the day to generate hydrogen, which is then used in a fuel cell to power homes at night. Because the hydrogen is produced from water and returned to water after it is used in the fuel cell, these systems consume few resources.

Tour says these are still early days for his laser-induced graphene sheets, but experiments have demonstrated enormous potential. Rice has already licensed the graphene technology to Houston-based PfP Technologies, which plans to initially use graphene to recycle water produced in oil fields.

Tour’s breakthrough is yet another example of how innovation is changing the energy landscape, and why the future does not have to rely on fossil fuels.

Chris Tomlinson is the Chronicle’s business columnist. chris.tomlinson@chron.com twitter.com/cltomlinsonwww.houstonchronicle.com/author/chris-tomlinson