TOWARD the LIGHT

FORMER CHURCHES ARE REBORN AS HEAVENLY RESIDENCES THANKS TO A VISIONARY DEVELOPER

BY LEILANI MARIE LABONG

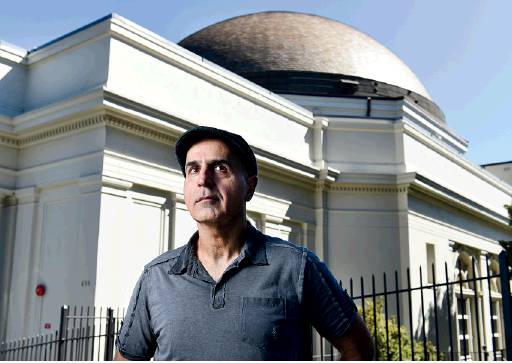

In 2001, Siamak Akhavan spent an hour in the King’s Chamber, located near the zenith of the Great Pyramid of Giza, marveling at its construction. As an engineer, he found the ancient architecture, with its precise arrangement of 50- to 80-ton granite blocks, almost unfathomable. That night, he couldn’t eat or sleep. “My entire metabolism and energy changed,” says Akhavan. “I felt supercharged.”

One of the best ways to harness the natural power of a planet, he explains, is with a pyramid — the shape is a natural amplifier of electromagnetic waves. But even in the absence of such an architectural wonder, Akhavan claims that the energy of a building — any building — is a very real thing.

We’re experiencing this first hand, as we banter about world history and psychic abilities in his 4,500-square-foot loft under the dome of the former Second Church of the Christ, Scientist overlooking Dolores Park.

Akhavan has newly christened the early 20th-century neoclassical building, which he purchased in 2011 for $2.3 million (approximately $500 per square foot!), “The Light House,” because erstwhile sanctuaries never really shed their roles in the community as radiant beacons of hope, even if, like this one, they’ve been developed into four condominiums up to 5,400 square feet in size. And also because the city’s historic preservation commission required the original brass signage — along with every stained-glass window, water fountain, door hinge and keyhole — to be somehow retained in the new residential design, a painstaking negotiation that took nearly two-and-a-half years. As such, the current name of the building is, with some creative finagling, a rearranging of some of the letters of the name that previously graced the front of the building.

“People used to gather here to pray, celebrate, worship and mourn,” says Akhavan, a native of Iran and a political dissident turned seismic engineer turned real estate developer who moved to the Bay Area in 1991. “They left their imprint, just as we will leave ours. Although you can’t see the energy, it’s still around. You can feel it, right?”

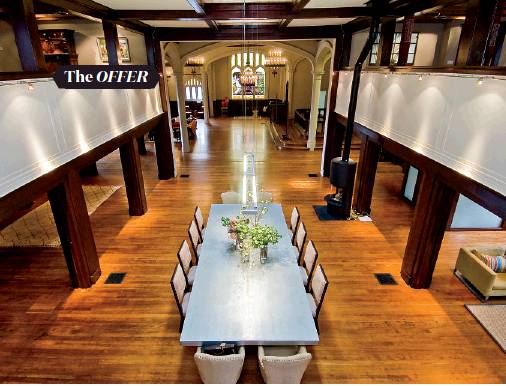

It’s profoundly quiet here, due in part to the solid 1917 concrete-and-brick construction. To behold its structural might, we quickly survey one of the century-old retaining walls, absent of cracks and moisture — a befuddling feat of old-timey engineering. To bring the building up to earthquake code, Akhavan orchestrated a seismic retrofit that included, among other major reinforcements, eight new exposed steel frames that lend a timeworn patina to the residences.

The building’s distinctive hush is also owed to the reverence that’s simply part of its fabric. The original design by architect William Crim eschews religious iconography for more inclusive, classical motifs such as floral patterns in the stained glass and exterior Greek columns. The central dome is also a standard fixture for of-the-era Christian Scientist churches, serving as the original building’s main source of natural light. “The only reason I took on this project was to be under this dome,” says Akhavan, who is as thrilled about living under its generous curve as he is about the beauty of the mechanics holding it up, a complex system of turnbuckles and trusses and tension rings that can be examined up close on the loft’s small mezzanine.

Given his penchant for history and hallowed ground, Akhavan is no stranger to restoring churches. Looking from the north-facing windows over the landscape of the Mission District, he points to the brick tower of the 1910 Norwegian Lutheran Church in the foreground. He helmed a team of engineers and artisans to bring its Gothic architecture back from the brink in 2007, devoting special attention to the ornate brick facade, painted ceiling, stained glass and faux bell tower.

Unable to sell the property during the economic downturn, Akhavan took up residence for a spell, loosely channeling the life of Gorodish, a character in the 1981 French thriller “Diva,” who lives in a large loft that his girlfriend traverses in roller skates. “We turned that church into a 17,000-square-foot home. I could have used the roller skates!” says Akhavan, who sold the property in 2011 to Children’s Day School for $6.6 milion, a significant reduction from the original $9.95 million asking price. “I didn’t really mind because it was going to a school,” says the 54-year-old, who, along with a group of high-school buddies, has partnered with Bay Area-based Mothers Against Poverty to build schools in Iran. “And I hear the kids call it Hogwarts.”

Ever mindful of the linear nature of time, Akhavan likens the history of his churches to a long narrative. At press time, the last of The Light House’s condos, 653 Dolores, had sold to a tech kingpin for $6.1 million, the painters were patching up the renovation’s last scuffs and dings, and Akhavan was on his way to Iran for an archeological dive in the Persian Gulf. Now in the hands of its new keepers, the latest chapter of The Light House is connected, like in any good story, to its beginning. “It was a sanctuary then, and it still is today,” says Akhavan.