Sustainable communities growing

State organization certifies 22 municipalities in inaugural year

By Randall Beach

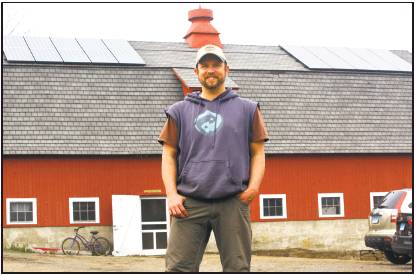

WOODBRIDGE — Steve Munno calls himself a “steward of the land,” not simply a farmer.

Munno, the farm manager at Massaro Community Farm, where he also lives, is a key part of why Woodbridge has been certified as a sustainable community by the organization Sustainable CT.

Under this voluntary program, 22 municipalities in the state applied for and received certification in 2018, the inaugural year of the effort. Other communities in Connecticut include Fairfield, Greenwich, Ridgefield, Stamford and Westport in Fairfield County; Madison, Milford and New Haven, also in New Haven County; Bristol, Glastonbury and Hartford in Hartford County; Middletown and Old Saybrook in Middlesex County; Roxbury and New Milford in Litchfield County; West Hartford and South Windsor in Hartford County; Coventry and Hebron in Tolland County; New London and Windham.

In addition to certifying municipalities for their work, Sustainable CT aims to provide them “with a menu of coordinated voluntary actions to continually become more sustainable; to provide resources and tools to assist them in implementing sustainability actions and advancing their program for the benefit of all residents,” the program’s website says.

In this time of climate change and its devastating consequences, that mission is more essential than ever, noted Jon Gorham, who heads the Woodbridge Ad Hoc Sustainability Committee. He is also president of the Massaro Community Farm.

“We would like to have a future for our children,” Gorham said. “We’ve got kids who are asking: ‘What the hell are you old folks doing, handing over a planet to us that’s going to die?’ They’re angry because we’re possibly giving them an unsustainable world.”

But Gorham said younger people aren’t waiting for their elders to do something.

“Students at Amity Regional High School’s Amity Global Warming Club spearheaded efforts to get solar collectors installed at their school,” he said.

After years of advocacy, the solar panels were installed in 2010.

Woodbridge has a half-dozen major buildings that now have solar panels, Gorham noted. These include Beecher Road Elementary School, the town library, the barn at the Massaro Community Farm and the Jewish Community Center of Greater New Haven, where Gorham was interviewed for this story.

“The solar collectors on this building,” Gorham said, pointing upward, “saves the JCC $35,000 per year in energy costs. They were installed for free by a company from Germany.”

The Massaro Community Farm was able to become a demonstration piece for good environmental practices because people in Wood-bridge saw an opportunity when the town acquired the abandoned 57-acre property in 2007.

“The barn had collapsed,” Gorham said. “But we set up a nonprofit, got a $5,000 grant, fixed up the barn and house and leased the property from the town. By 2009, we were in business!”

The residents raised $1.1 million because, Gorham said, “It costs that to keep a farm up and going.” He added, “That farm is a big piece of what we’re doing with sustainability.”

“Local farming is the future,” Gorham said.

Munno, now is his 10th year working the Massaro Community Farm, pointed proudly to the eight solar panels atop the restored barn.

“They help reduce our carbon footprint,” he said. “We’re trying to do as much as we can in an environmentally friendly way.”

He said, “We’re sensitive to the needs of the soil, keeping it covered and protected. We’re not killing off weeds with pesticides. It’s all about: what kind of steward of the land do you want to be?”

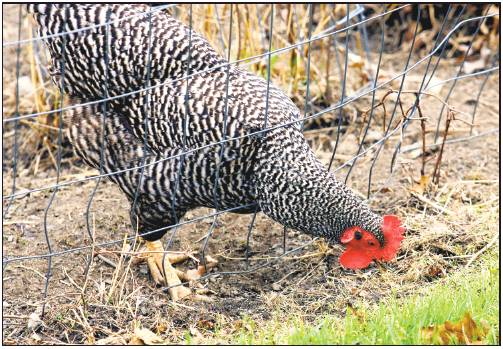

Munno is also pleased the farm creates a habitat for bees, butterflies, birds and all sorts of mammals. “A black bear walked by here about 20 minutes ago,” he said.

Munno enjoys living in the small farmhouse with his wife, Jacquelin, and their daughter, Vivian, who is not quite 2 years old. “We love it and our daughter loves it, exploring the wildlife.”

The farm is also open to the public, accepting visitors during daylight hours to check out the operations and walk the trails. On the day Munno was being interviewed, Antonio Librandi stopped by with his grandchildren, Maxi-mus and Gulia Figueroa, to feed the hens.

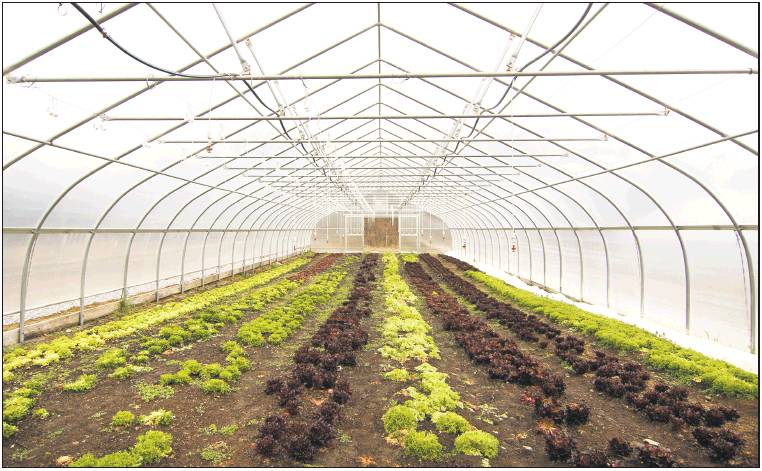

“We’ve got an afterschool program, a summer camp and workshops,” Munno said. “And we’ve got about 200 subscribers who (for a fee) pick up our produce. We grow about 50 different kinds of vegetables. We also sell to restaurants in the New Haven area and we sell at farmers markets. We donate about 10 percent of our produce to hunger-relief organizations and soup kitchens.”

Like any farmer, Munno has learned to contend with difficult and unexpected weather patterns. Last year was unusually wet.

“We got about 8 to 10 inches of rain per month, double what we usually have,” he said. “The soil got saturated; our carrots were getting flooded out. The fall was particularly tough on our spinach and carrots ”

Gorham called it the worst growing season the farm had experienced since it was revived 10 years ago. “We had extreme heat and massive rains; 6.4 inches of rain in one day. So we’re experiencing climate change here in Wood-bridge.”

Given the stakes for the planet, Gorham is impatient with the pace of other municipalities participating in Sustainable CT.

“We’ve got 169 municipalities in Connecticut and only 22 certified,” he said. “Some towns have risen to the occasion. Let’s get everybody going on this!”

But Lynn Stoddard, who helped launch Sustainable CT, said 83 municipalities are now registered, including the 22 who have been certified. Being registered means a resolution has been passed stating the municipality wants to participate in the program and local officials have designated a liaison to work with Sustainable CT.

“That’s almost half the state,” Stoddard said of the 83 figure. “We’re seeing a lot of great momentum.”

Stoddard noted Sustainable CT is not a state agency. It’s run by the Institute for Sustainable Energy at Eastern Connecticut State University; she is its executive director.

Sustainable CT’s website documents how Madison earned its 230 points to get certified. Examples: 15 points for supporting redevelopment of brownfield sites; 15 points for watershed protection and restoration; 10 points for developing an open space plan; and 25 points for developing agriculture-friendly practices.

Stamford was certified in October with 535 points, including 30 each for engaging in watershed protection and restoration and implementing low impact development; 15 points for assessing climate vulnerability, developing an open space plan and mapping tourism and cultural assets, among many other initiatives, according to Sustainable CT.

Also in Fairfield County, Greenwich was certified in October with 410 points. This included 40 points for creating a plan for recycling additional materials and composting organics; 35 points for promoting effective parking management, 25 points for improving air quality in public spaces and 10 points for encouraging smart commuting, among other initiatives. An example in Greenwich included a 2018 initiative in which the Greenwich Public Schools’ PTA Council Green Schools Committee conducted a pilot program at Cos Cob School to institute “Foam-Free School Lunch” to exclude the use of “polystyrene food trays, aka Styrofoam,” according to information available from Sustainable CT.

During this pilot that lasted about two months, “With reusable trays and the sorting center, recycling dropped 60% and trashed dropped 86% by volume,” the Greenwich district reported to Sustainable CT.

Fairfield was certified with 560 points, and Westport with 345 points, both also in October.

New Haven’s 555 points included: 20 points for creating a watershed management plan; 25 points for supporting arts and creative culture; and 50 points for high energy performance for individual buildings, such as public schools.

In Hamden, the town’s energy efficiency coordinator, Kathleen Schomaker, has been leading the effort to get the town certified this year in time for the Aug. 30 deadline.

Asked why it’s important for Hamden to pursue this work, Schomaker replied in an email: “Economic development benefits; broader community engagement with nature and ecological stewardship; enhancing social equity and community resilience — all are desirable outcomes from this process.”

Stoddard said 13 states now have sustainability programs, and representatives meet occasionally to talk about each state’s efforts and progress. “We learn from each other.”

Stoddard noted the psychology involved in encouraging towns to amass points as they work to get certified. “We’ve set up a competition. They like to brag they’ve gotten certified, compared to their peers.” randall.beach@hearstmedia ct.com