Photos recount portraits of Jews on eve of Holocaust

JANE KAUFMAN | STAFF REPORTER jkaufman@cjn.org | @jkaufmanCJN

On the eve of deportations to concentration camps in 1943 and 1944, German Jews who had immigrated to Amsterdam made their way to an apartment near a three-way intersection.

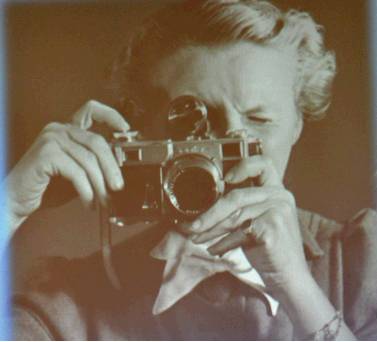

Wearing the mandatory yellow stars under Nazi occupation, more than 400 people had their portraits made by Annemie Wolff, who had emigrated from Germany and whose husband, Max Wolff, a Jew, committed suicide after Germany took control of the Netherlands.

For decades, Wolff’s wartime photos remained privately held.

It wasn’t until Simon Kool, a photographic historian, contacted the granddaughter of Wolff’s former neighbor that a register and hundreds of photographs were unearthed dating from that time.

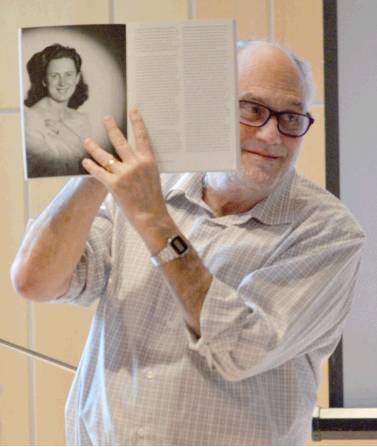

“And then they found rolls of film … in which there are all kinds of portraits,” Rabbi Peter Haas told about 80 people gathered for the Jewish Genealogy Society of Cleveland’s monthly meeting Jan. 12 at Park Synagogue East in Pepper Pike. “And they realize that the register is a register of portraits that she took of German Jewish refugees during this period.”

Anthropologist An Huitzing and her daughter, historian Tamara Becker, have traced the stories behind at least 300 of the faces.

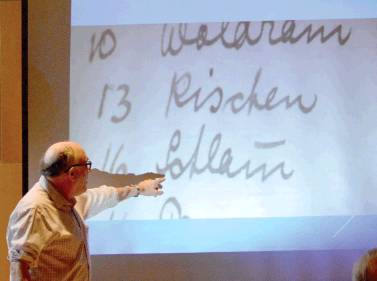

Three of them – Vera Schlamm, Marga Schlamm and Meta Schlamm – were close relatives of Haas.

Huitzing wrote Haas in 2014 asking if he recognized a photo of Vera Schlamm, who was his aunt. And since then, Huitzing and Haas have connected, with Huitzing showing Haas the building in downtown Amsterdam where his father served as a bicycle mechanic, and the buildings in which his parents lived.

“So An Huitzing did a remarkable job of tracking down these families, finding descendants, showing them the pictures and getting people identified and in filling in the background of the story,” Haas said.

Haas, the Abba Hillel Silver professor emeritus of Jewish studies at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, presented a brief biography of Wolff as well as stories of some of those photographed in Becker and Huitzing’s book, “Op de foto in oorlogstijd, Studio Wolff 1943,” which was published in Dutch in 2017. It has not been translated to English. The title translates to “On the Photo in Wartime.”

Each chapter, Haas said, contains the register Wolff kept for that roll of film, photos and stories of the victims and survivors.

Huitzing and Becker saw to the placing of placards in the Riverbuurt neighborhood with the portraits of Jews and their names, similar to the stolpersteins, or stumbling stones, of Germany, which mark the homes of Jews prior to the Holocaust.

In addition, an exhibit at the National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam displays photographs of those whose stories are still unknown. Those who recognize the photos are asked to contact Huitzing.

Haas’ father, Eric Haas, emigrated from Germany to Amsterdam in 1935. There he met Marga Schlamm, another German refugee, at a wedding and the two married in July 1942 in the Hollandsche Schouwburg theater, the only place Jews could legally marry in Amsterdam at the time.

And shortly afterward, Haas believes, his mother sat for her portrait in Wolff’s studio.

Several photos were taken, including glamour shots where her wedding ring figures prominently and where she wore a shawl, possibly borrowed from the photographer.

Haas’ father, mother, aunt and mother’s parents stayed together despite their deportation to Bergen Belsen.

They were traded for German prisoners of war in the only such trade that took place from that German concentration camp, spending the rest of the war in a French displaced persons camp in Algiers.

Haas was born in Detroit and grew up in San Antonio. He graduated from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and received ordination from Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati. He lives in Shaker Heights.

To see additional images of the meeting, visit Facebook.com