PORT ARTHUR

Exhausted, steamed & litigated

Emissions concerns arise over a calcining plant as its deal to supply heat to a green energy producer sinks into an unending legal dispute in the heart of petrochemical country

By Kaitlin Bain

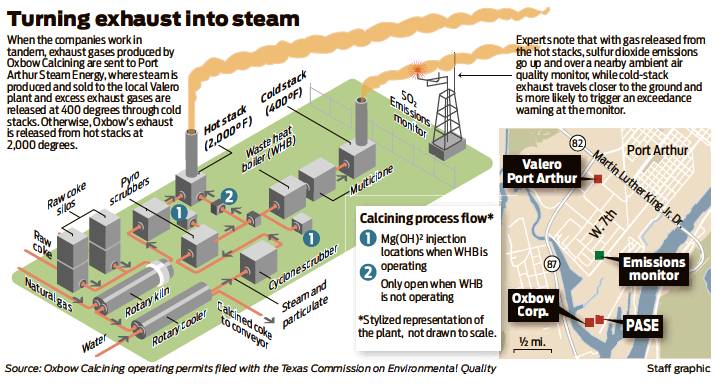

In 2005, a private company called Port Arthur Steam Energy began taking exhaust heat from one nearby plant and converting it into steam, which it sold to another plant to use in refinery processes.

The business arrangement had the side benefit of reducing the amount of carbon dioxide that would have been released to create the same amount of steam through traditional methods.

It was a green project in the heart of a vast petrochemical ecosystem, perhaps the nation’s highest concentration of refineries and other plants. It worked so well that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency gave PASE an Energy Star award, noting that the company eliminated the equivalent of 27,000 cars’ worth of CO2 emissions annually.

Fourteen years later, PASE is all but shuttered and 15 local workers have lost their jobs. It’s mired in a long-running contract dispute with Oxbow Calcining, the company it was getting the exhaust heat from. A major point of contention is whether Oxbow can legally deprive PASE of the raw material it needs to operate.

The fight also brought attention to a change in the way Oxbow sends another pollutant, sulfur dioxide, into the air. Activists don’t think the state’s environmental regulatory agency can adequately monitor the plant under this new normal.

“Oxbow’s intentions are clear,” now-retired Judge Donald Floyd, then of Jefferson County’s 172nd state District Court, said in a related court ruling a year and a half ago. “Oxbow intends to remain in business, operate … at any level it chooses by discharging (exhaust), avoid having to purchase or maintain pollution control equipment to control SO2 emissions and keep PASE from generating steam revenues.”

B B B

Oxbow’s Port Arthur calcining plant, on a 112-acre waterfront site near the Sabine Neches Ship Channel, uses petroleum coke, a byproduct from the oil refining process, to create calcined coke, which is then sold to make aluminum, titanium dioxide and other industrial products.

Sulfur dioxide and heat are two byproducts of this process.

Oxbow released more than 11,000 tons of sulfur dioxide into the air in 2016, according to calculations by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, making it one of the top 10 emitters of the invisible chemical in the state.

Sulfur dioxide makes breathing difficult, contributes to acid rain and reacts with other compounds to form small particles that can penetrate deeply into sensitive parts of the lungs, the EPA says. It also can react in the atmosphere to form aerosol particles, which can contribute to outbreaks of haze and influence the climate.

These releases alarm environmental activists such as Neil Carman, a former TCEQ investigator who is now director of the Clean Air Program for the Sierra Club’s Lone Star Chapter.

“I’ve been concerned about this plant for 25 years,” Carman said. “They emit nearly 85 percent of the SO2 in Jefferson County. Compared to the refineries’ emissions, they’re the big kahuna.”

The company decided in 2016 not to install scrubbers that would decrease the amount of sulfur dioxide released by its operations, citing costs. Estimates from PASE and Oxbow for the pollution-control measures range from about $27 million to $56 million in capital expenses, excluding any contingencies or cost overruns.

Asked about the decision to forgo the scrubbers, Oxbow spokesman Brad Goldstein told The Enterprise that the company is in full compliance with its operating permits.

“We are proud of our environmental record and continue to work proactively with TCEQ to operate within all applicable laws and permits,” he said in an email.

Goldstein wouldn’t comment on the amount of sulfur dioxide released by the plant.

B B B

Sulfur dioxide monitors set up by the TCEQ are supposed to log when the surrounding air has more than 75 parts per billion of sulfur dioxide — the national standard set in 2010. Jefferson County could be considered out of compliance should any of its monitors exceed that limit three times in a one-year period.

The EPA mandated that many of these monitors be placed near sources that, like Oxbow Calcining’s Port Arthur plant, emit more than 2,000 tons per year of sulfur dioxide.

The TCEQ determined where to put the monitor to catch the highest sulfur dioxide concentrations by using Oxbow’s operating procedures at the time, according to the agency’s 2016 Annual Monitoring Network Plan.

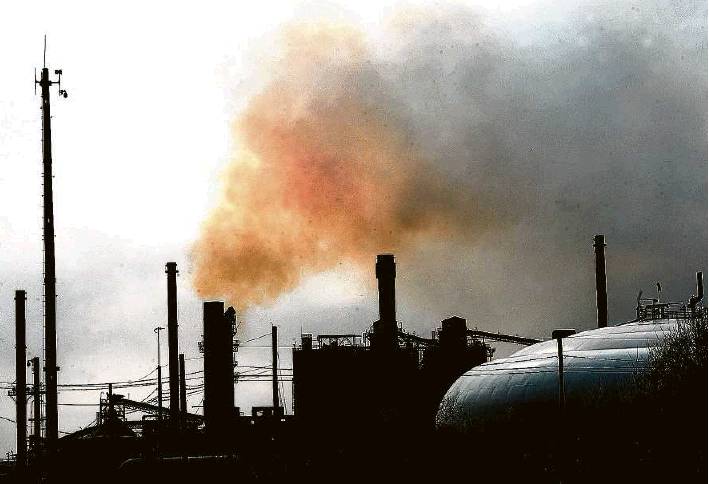

The plant was releasing its emissions during this period at 400 degrees Fahrenheit out of three smokestacks and at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit out of a fourth smokestack, according to the plan and information from Oxbow’s operating permits.

The 400-degree Fahrenheit smokestacks belong to PASE, which is connected to Oxbow’s plant.

When the two plants are operating in tandem, Oxbow sends its exhaust gases to PASE, which extracts heat from the gases to create steam that it sells to the nearby Valero refinery.

When the exhaust gases go through PASE’s process, they’re cooled and released out the 400-degree “cold stacks.” When Oxbow bypasses PASE, the gases are released through the 2,000-degree “hot stacks.”

A contract between the two companies mandates Oxbow deliver its exhaust gas to PASE, unless the action would break a law or cause Oxbow to face legal action, according to PASE.

PASE and Oxbow have been in an on-again, off-again contract fight since 2011. Today, the fight is largely over whether Oxbow is contractually obligated to deliver its exhaust gases to PASE regardless of whether that would cause Oxbow to violate air quality standards.

The most recent iteration of this dispute started three years ago in part because Oxbow began bypassing PASE, leaving it with no product to sell. Many details regarding Oxbow’s release of sulfur dioxide emerged during public court hearings.

In an interview with The Enterprise, former PASE employee Kenneth Vallier, 60, who worked with the company for more than a decade, said he started getting periodic calls from Oxbow in 2016 saying it would be temporarily bypassing PASE’s system for testing.

He said he and other employees noticed that the company would say it was testing when the wind was blowing a certain way that would make the monitor more likely to pick up the sulfur dioxide.

“It got to the point where we could look at which way the stacks were blowing and know if Oxbow was going to be shutting the dampers on us,” Vallier said.

Oxbow spokesman Goldstein declined to respond to the allegation on the record.

In November and December 2016, the first two months the sulfur dioxide monitor was in operation, Oxbow went above the sulfur dioxide limit six times, TCEQ records show. The company exceeded the limit six times in 2017 and three more times in the first four months of 2018.

After that, the company completely discontinued sending exhaust gas to PASE.

The company said in court documents that it determined, while working with state regulators, that releasing the emissions through the cold stacks caused the sulfur dioxide exceedances.

Ray Deyoe, managing director of Integral Power, which manages PASE, testified during one court hearing that the same amount of sulfur dioxide is released from hot or cold stacks.

The difference, noted by Deyoe and Carman, the environmentalist and former TCEQ investigator, is that sulfur dioxide likely goes up and over the monitor when released at the higher temperature. The gas ends up at a higher concentration farther away, Carman said.

“I believe that SO2 hourly air monitoring would likely predict that SO2 hourly violations may be occurring at a different west Port Arthur site than the existing SO2 monitor,” he said. “TCEQ knows all these details since this is their business.”

Goldstein said Oxbow’s duty is to comply with environmental standards, even if that means using the hot stacks and bypassing PASE.

“We found the most expeditious way to fix the (sulfur dioxide exceedances) and get us into environmental compliance was to run through the hot stacks,” he said.

B B B

Goldstein cited pending litigation in declining comment on why it’s acceptable to operate out of the hot stacks despite the fact that TCEQ’s placement of the ambient air quality monitor relied largely on operations out of the cold stacks.

Judge Floyd wrote in his court ruling that these actions made it clear that Oxbow was using techniques to avoid sulfur dioxide detection by the state monitor. He said he was “troubled” Oxbow was able to move “the same pollution to another location.”

Another Texas environmental activist, Adrian Shelley of Public Citizen, said TCEQ could settle the matter if it wanted to.

“But it would not be at all surprising if they took a ‘Hear no evil, see no evil’ approach and didn’t show where that dispersion is going,” he said.

Asked why the monitor was placed in its current location, TCEQ pointed to the 2016 modeling report, which shows the monitor’s placement based on since-changed operations.

“Placement of the monitor was based on Oxbow’s representation of its operations under its air permit at the time the monitor-siting analysis was performed,” agency spokesman Andrew Keese said.

Keese reiterated later that Oxbow is permitted to operate out of the hot or cold stacks.

Questioned further about how allowing Oxbow to operate solely out of hot stacks fits with the intent of the monitor’s testing, Keese said the monitor near Oxbow is not meant to capture solely emissions from Oxbow.

“These monitors are placed to measure ambient air concentrations of specific pollutants that may originate from avariety of sources in a given area (industrial sources, trucks, ships, etc),” he said in an email. “Placement of a monitor downwind and near to these sources would capture the impacts on ambient air concentrations of all emissions from these sources.” kaitlin.bain@beaumontenterprise.com twitter.com/KaitlinBain