Getting There

Relatives show toll of drivers texting

Ben Wear

No jokes today.

On Thursday, I sat through what has become a wrenching biennial tradition at the Legislature, a gathering of grieving Texas parents, children, brothers and sisters and others whose relatives died in traffic collisions caused by someone using a cellphone while driving. Sometimes the victim was the person using the phone, sometimes the other driver. That detail really doesn’t matter in such cases, or at least it shouldn’t matter to policymakers.

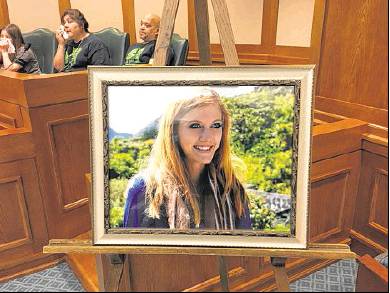

The event was held in a Capitol hearing room adorned, if that’s the word, with pictures of those who died. Their loved ones sat behind those pictures on the dais, often dabbing their eyes as others spoke. We heard about text messages and Snapchat and the crashes that followed, about youthful laughter silenced, potential extinguished, about knocks on the door from state troopers, horrifying news delivered in emergency rooms and regular visits to grave sites. There were a lot of tears, including from reporters. There was a lot of anger as well.

“I’m getting pissed, because this is outrageous,” said state Rep. Gene Wu, D-Houston.

“This” refers to the decisions by the Legislature and a former governor to reject legislation in 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2015 that would have made cellphone use while driving (other than hands-free devices, or to report crimes or emergencies) a misdemeanor under state law. The state already outlaws it for 16- and 17-year-old drivers, and for anyone passing through a school zone. Federal law carries steep fines and the loss of commercial driving privileges for truckers and bus drivers who do it.

And, according to an insurance lobbyist at the meeting, 95 Texas cities have banned it.

Even so, about 10 percent of fatal crashes nationwide in 2013 were caused by distracted driving, according to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates, with phone use being that distraction most of the time. The total loss of life on Texas streets and highways last year reached 3,700, Houston Senior Police Officer Don Egdorf said at the event.

As for how many of those might have been related to phones, Egdorf said even police can’t say for sure. Survivors often decline to admit to the role of their cellphones in collisions, he said. And often there is no one left to offer such testimony. The practice, he said, is “underreported.”

“This is something that has to stop,” Egdorf said. “These are not accidents. It’s an intentional act.”

State Sen. Judith Zaffirini, D-Laredo, has been carrying a so-called “texting” bill since the 2009 session, joined since 2011 by former House Speaker Tom Craddick, R-Midland. In 2011, they got a bill all the way to the desk of then-Gov. Rick Perry, who vetoed it because it was “a government effort to micromanage the behavior of adults.”

After the legislation in 2013 failed to get out of a Senate committee, Craddick in 2015 passed his version through the House on a 102-40 vote, and Zaffirini had 18 commitments in the 31-member Senate. But Senate rules require 19 votes to bring a bill up for debate. State Sen. Konni Burton, R-Colleyville, corralled a group of mostly junior senators into a “freedom caucus” that wouldn’t budge in their opposition, and Zaffirini fell that one vote short of bringing the matter to the floor where it almost certainly would have passed.

So now, in the 2017 session, Burton is said to be marshaling opposition yet again. Her office declined to comment Friday. But in 2015, Burton raised the specter of police using the law as a pretext for unconstitutional searches of people’s phones. The Craddick and Zaffirini bills specifically prohibit police from taking a phone or inspecting it, absent already existing authority under Texas criminal law.

If that has occurred with any regularity in the 46 states that already have such statewide bans, or in all those Texas cities that now make it illegal to drive and use a hand-held phone (including, for the past two years, Austin), that alleged police abuse of the law has failed to generate a groundswell of outrage. What has occurred in recent years, many said last week, is ever-increasing ownership of smartphones.

That means drivers, who as recently as 2010 might have been tempted only to talk or text while driving, now have the added lure of social media and, in this era of all-Trump-all-the-time-news, articles that just demand to be read on their phone. Right now. Leading, more than once a day in Texas on average, to tragedy.

James Shaffer was the last to speak Thursday.

His wife, Emma Shaffer, and their daughter, Tita, who was 12, were killed April 9 on U.S. 377 in a head-on collision near Denton. Shaffer said investigators concluded that the other driver had just sent a text, and had received another, within three minutes of when witnesses reported that her car swerved over the center line and hit the Shaffers. The other driver and her 4-year-old daughter also died in the crash.

Shaffer, fighting back tears throughout his talk, said the hardest thing he had ever had to do in his life was tell his 10-year-old son Jimmy the next morning that his mother and sister weren’t coming back. He said the boy in the months since has told him, more than once, that he wishes he had a time machine so he could go back and warn the other driver not to use the phone.

“I can’t do that,” Shaffer said, “but I can make a difference today. I would do anything to have my girls back, and to take away my son’s pain.”

Contact Ben Wear at 512-445-3698.

Twitter: @bwear