growth

Caught in county’s boom

Some in Saratoga County’s towns straining under the pressure of new housing

By Wendy liberatore

Dawn Ulrich describes her 1880 cottage in Stillwater hugged by woods and bordered by a stream as her dream home. But within less than a year of living there, she was fighting for its preservation.

Ulrich joined the chorus of dozens of residents last February who pleaded with town officials to stop a plan to plow down the forest surrounding her home to make way for a development of 21 single-family homes.

“I didn’t move here to live in suburbia,” she told elected officials.

But the board was unmoved and the White Sulphur Springs development was unanimously approved.

“It’s a terrible shock,” said Ulrich outside of her Luther Road home. “I love my home, it means a lot to me and to hear about the development and a boulevard that will run through here, it breaks my heart.”

Ulrich is not alone. She is among scores of Saratoga County residents who faithfully attend public meetings to petition elected officials to stop the encroachment of housing developments. The residents, who live in towns that run along the Northway corridor, are arguing against the creep of subdivisions for more reasons than personal ones. They fear the pace of development is destroying farms, forests, fields, the watershed, and ultimately, threatening the quality of life.

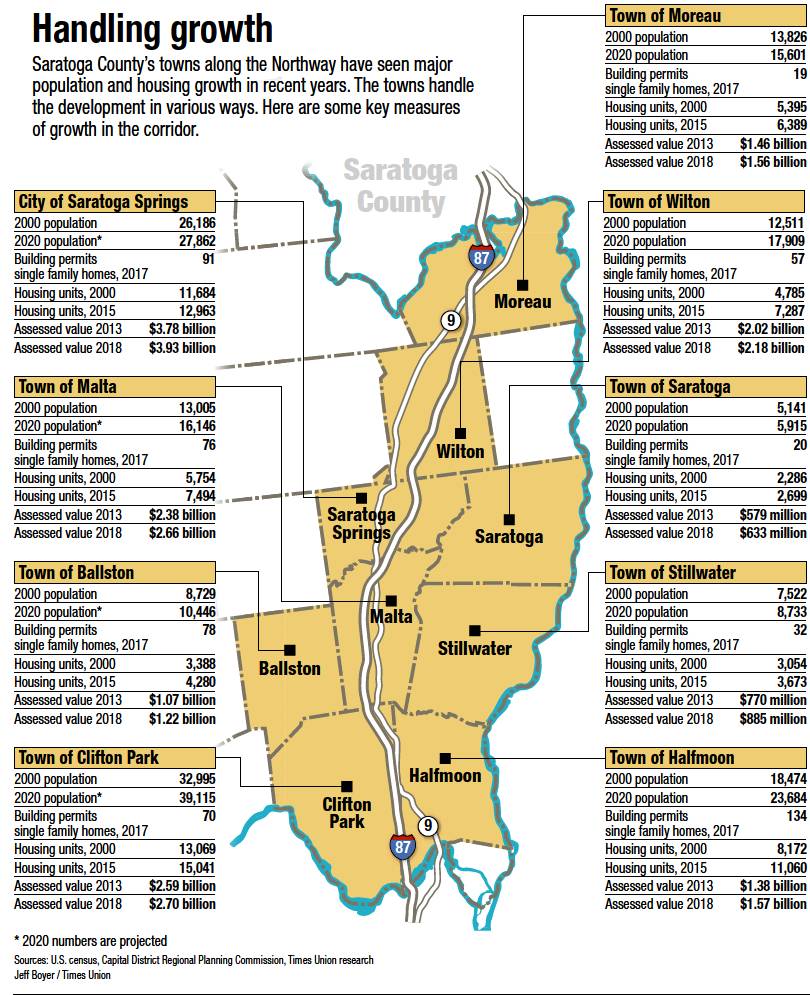

This is nothing new. The build-up of housing in the county has been unstoppable for years. The U.S. Census Bureau calculates that about 123,000 people lived in the county in 1970. Population rose to 153,759 in 1980, then 182,276 in 1990 and 200,635 in 2000. By 2020, the Census Bureau predicts the county will be home to 234,358 — nearly doubling its 1970 figure. That averages out to 30,000 new residents moving here every 10 years.

The bureau also confirmed that the county continues to be the state’s fastest growing outside of the New York metropolitan area. This influx brings pressure for housing.

Are there tax benefits?

While residents would argue the county has reached a tipping point, the county’s elected officials, most of whom are Republican, say the county can add more homes and can do it in a way that preserves the landscape. And that they must, otherwise taxes will have to go up.

“We don’t want to be at a static point,” said Ed Kinowski, Stillwater Supervisor and chair of the County Board of Supervisors. “Everything is going up .... to maintain the services that people expect, we have to grow. We want Stillwater to grow steadily so we can keep taxes low or not raise them at all. If we don’t have development, we’ll have to raise taxes.”

The county’s low tax rate is one of the virtues that county politicians love to tout. Wilton Supervisor Art Johnson said that people are lured to the county because of the taxes. He said the low taxes need to be preserved as much as the landscape.

“We don’t have a town tax or a highway tax,” said Johnson whose town ranked as the sixth fastest growing in the county with a 5.2 percent rise in population in 2017. “If we don’t grow, we can’t keep our taxes low. It is important.”

Johnson said the key to balancing growth and taxes is well-defined and continually updated comprehensive plan. The guidance from the plan should ensure “commercial growth does not encroach on residential growth” and that green space is preserved.

“We slowed down because we need to take a breather,” Johnson said of Wilton. “We don’t want to grow too quickly because it can become a strain on our infrastructure and become more costly. It comes down to balance and listening to feedback from the public.”

Studies show that housing developments can cost more than they bring in. A 2006 study from the University of Georgia noted that local governments are trying to fix their fiscal woes by increasing their property tax base.

“A growing body of empirical evidence shows that while commercial and industrial development can indeed improve financial well-being of a local government, residential development worsens it,” states the introduction to The Fiscal Impacts of Land Uses on Local Government. “While residential development brings with it new tax (and fee) revenue it also brings demands for local government services,” the study reads. “The cost of providing these services exceeds the revenue generated by the new houses in every case studied.”

Another study from the School of Urban and Regional Planning of Queen’s University in Ontario looked at housing in the U.S. and Canada and found that housing developments have increased congestion and pollution and raised the cost of services. It also concluded “the push without end through old orchards, farmland, forest and meadows” is “killing the golden goose” that brings people to the area in the first place.

Affordability vs. luxury

Wilton’s balanced approach will not prevent new subdivisions. Its planning board is considering a 310-unit subdivision proposal between Jones Road and Putnam Lane on a tract of 550 acres, mostly wooded.

Peter Belmonte, who wants to build the mix of single-family homes and townhouses, described it as a “premier subdivision of the Capital Region.”

The deeper into the subdivision one goes, the more expansive and expensive the homes will be.

This poses yet another problem, said Art Holm-berg, chair of Sustainable Saratoga, anonprofit that advocates for sustainable practices to protect natural resources for future generations. Wilton, like Saratoga Springs, has shifted construction to cater to the luxury buyer.

“Houses that are a half million or three-quarters of a million dollars do not open up the housing market to everyone,” Holmberg said. “A sustainable city includes diversity, more younger families, diversity of age and race. Saratoga is becoming a very gray city that is attracting retirees from Westchester and New Jersey.”

He said the city is building workforce housing on West Avenue and South Broadway. But he adds, the housing is relegated to the outskirts.

“It’s creating a segregated city,” he said.

A study of housing in Saratoga Springs, Housing Needs: Saratoga Springs Market, has found that 72 percent of affordable housing units in Saratoga Springs are designated for seniors. This coincides with the construction of luxury housing units for seniors including The Summit at Saratoga, which is actually in Wilton, and Station Park, which is being planned near the train station on West Avenue.

While no Saratoga Springs officials, including Mayor Meg Kelly, would comment on the vision for the city’s development, Holmberg said that right now most of the development is concentrated in the city’s center. He worries about what will happen once the main streets are saturated.

“If development kept to the urban core, that’s sustainable,” Holmberg said. “If it goes out into the area of the Greenbelt trail, then that would not be good. We would really fight against that.”

With green space becoming more of a priority, some towns have turned to the nonprofit Saratoga PLAN, which has a mission to preserve the rural character of the county by identifying areas to conserve and then helping towns to devise a plan to achieve that.

Stillwater, where White Sulphur Springs will be built, is among the towns that have consulted with the nonprofit. So too has Ballston, which is steeped in a legal battle with the state Department of Agriculture & Markets over a water line extension in the agricultural district. Ballston officials, who meet under a logo reading “a farm first community,” are also asking farmers to be development-ready, by subdividing their land into two-acre lots if they want to build a home for family members working on the farm.

“Conceptually, the towns want to preserve open space, but when it comes down to zoning, a lot of towns fall short,” said Maria Trabka, Saratoga Plan’s executive director. “You can’t zone everything into two-acre lots and achieve conservation goals, preserve the rural character or the view shed.”

A shift in Clifton Park

The outlier appears to be Clifton Park, the town many critics of development point to when arguing against growth. Supervisor Phil Barrett said he is “looking decades into the future” and has shifted his goal away from subdivisions and is now focused on preserving open spaces.

“Our job is to increase the value of Clifton Park,” Barrett said. “We want 33 percent less units over time and we want to design a town to promote contiguous open space that is either town owned or privately owned. The goal, years ago, was parks and recreation and trails. And that continues to be the initiative.”

Clifton Park, however, is sandwiched between a growing Ballston and Halfmoon. That increases traffic throughout Clifton Park, Barrett said, which is another item on the long list of complaints from residents who want development to slow.

Traffic is one of the main reasons Milton residents don’t want a 52-unit senior housing project on Hutchins Road.

“There is too much on the road,” said Dorothy Christiansen, who lives at 126 Hutchins Road. “It’s like a speedway now because people use Hutchins Road to go between Rowland Street and Route 50. We are a small neighborhood and one of the oldest neighborhoods in Milton. We have single family residents, some with second generation owners. (The housing project) is too much.”

Halfmoon Supervisor Kevin Tollisen said commuter traffic clogs his roads too and must always be considered before committing to development.

“We have made tremendous strides in making improvements to traffic in many areas of town,” Tollisen said. “We need to be cognizant and make strategic plans to continue to address traffic. We continually work with DOT and developers to find ways to improve traffic.”

Halfmoon remains the fastest growing of all the towns in Saratoga County with an increase of 13.5 percent in 2017, the Capital Region Economic Planning Commission calculated.

Tollisen said there are plans to ease traffic with a $1.8 million improvement at the intersection of Sitterly and Woodin Road that will add a new turn lane and new traffic signals. Route 146 in Clifton Park will also get some relief when a $3.82 million roundabout is installed at the intersection with Route 146A and Vischer Ferry Road.

Recently, there has been pushback on the rapid pace of growth in Halfmoon. In August, Town Councilman John Wasielewski, along with fellow board member Jeremy Connors, opposed Betts Farm, a 201-unit development on Route 236.

“It’s too much,” Wasielewski said. “The amount of units and the amount of traffic it will cause; we don’t have to jam every single area of open space with development.”

“We don’t want to be at a static point. Everything is going up ... to maintain the services that people expect, we have to grow. We want Stillwater to grow steadily so we can keep taxes low or not raise them at all. If we don’t have development, we’ll have to raise taxes.”

— Ed Kinowski, Stillwater Supervisor and chair of the County Board of Supervisors

Saratoga resident John Cashin, who is battling the 31-home Cedar Bluff subdivision that will be built on a ridge overlooking Saratoga Lake, said there should be more consultation between towns when it comes to development.

“From the standpoint of the county, it’s uncontrolled, uncoordinated.” Cashin said. “If the towns don’t coordinate and don’t consider the cumulative effects on our watershed, our trees, streets, it will be a disaster for recreation and tourism.”

Board of Supervisors Chairman Kinowski, who believes there is more room for housing developments without threatening the rural landscape, said the people will ultimately decide.

“When people say enough is enough, it will stop,” Kinowski said. “But that will probably mean a tax increase.”

Ulrich, however, doesn’t believe residents have any say.

“It’s a sham,” Ulrich said. “You go to express an opinion, but they don’t care.”

• wliberatore@timesunion.com • 518-454-5445 • @wendyliberatore