DISABILITY BENEFITS

A long, anxious wait

Backlog of disability applications mires thousands in a process that can take years

By Madison Iszler

Clemons

On the 615th day, Joseph Lestingi woke up hoping things would be different.

He got dressed. He straightened the couch cushions and tidied up the house while his wife was at work teaching at a nearby school. He strummed his guitar and spent some time with friends. He considered fixing the chimney, but that required clambering up on the roof with arthritic joints.

Finally, he shuffled to the mailbox, hoping for a letter with a date — the day of his Social Security disability hearing. When he came up empty-handed, he was disappointed but not surprised. It meant another day of waiting to plead his case before a judge, months after filing an appeal, more than a year after being denied benefits.

“I’m used to waiting,” he said. “You find ways to pass the time or you’ll go crazy.”

He never imagined he’d be sidelined with injuries that left him unable to tie his right shoe or play basketball with his grandson. For 24 years, Lestingi, 57, worked at paper mills, monitoring machines and testing the strength of chemicals at a job he enjoyed.

Then one day in 2011, he slipped and fell on a patch of ice while walking into work. For the rest of his 12-hour shift his right hip and leg ached, and the drive home was agony. The pain persisted for months, but he put off filing for workers’ compensation, convinced it would get better. It didn’t. He was fired, Lestingi said, while he was out of work for a year recovering from meniscus surgery on his knee.

It took a toll on his family of seven. Lestingi started taking money out of his retirement account to pay bills. He canceled their television package, got a free SafeLink cellphone and began using food stamps to get groceries. He applied for jobs online, but rarely heard back. Eventually he started receiving unemployment benefits.

In the meantime, Lestingi had developed arthritis in his hip and knee and was trying to avoid a hip replacement. Finally, in March 2016, he decided to apply for disability benefits. Five months later, his application was denied, and the next month he requested a hearing before a judge.

Two years later, he is still waiting for his hearing.

“I didn’t want to apply, but I feel like I was forced into it,” he said. “I never thought I’d be here.”

A waiting game

Lestingi is among hundreds of thousands of workers nationwide who are seeking disability benefits, according to federal data. The process often takes years. People have depleted their retirement savings, declared bankruptcy, lost their homes and even died waiting to receive benefits, said Mike Stein, assistant vice president of operations strategy and planning at Allsup, an Illinois-based company that represents claimants. In 2016 and 2017, according to federal data, more than 18,000 people died awaiting benefits.

“People are paying a price,” Stein said. “This has a severe impact.”

Kate Button, an attorney at the Law Firm of Alex Dell in Albany, said she has had several clients die while waiting. From the outset she tells clients they could face a long wait.

“It’s heartbreaking,” she said.

There are two federal disability programs, each with different requirements: Social Security Disability Insurance, which provides benefits for workers unable to work because of health issues, and Supplemental Security Income, which is based on financial need and is designed to help older citizens, the disabled or the blind. The number of people receiving benefits through the programs has risen from 11.5 million in 1995 to 18.5 million in 2015. Across the nation more than a million people are awaiting a hearing decision, caught in a backlog the Social Security Administration has called a “public service crisis.”

“It’s frustrating,” Lestingi said. “We’re eking by, but I’m not prepared for the future.”

Applicants are usually older, often have more than one disability, tend to lack health insurance and are more likely to be blue-collar workers with lower education levels, said Lisa Ekman, director of government affairs at the National Organization of Social Security Claimants’ Representatives.

After someone files an application, a state agency reviews it during a two-stop process, which usually takes three to six months. About two-thirds of claims are denied.

If they’re rejected, New Yorkers can request a hearing with an administrative law judge. The chances of being approved for benefits are “significantly better” in this stage, but they often face a long wait, said Ira Mendleson, partner at Buckley, Mendleson, Criscione and Quinn in Albany.

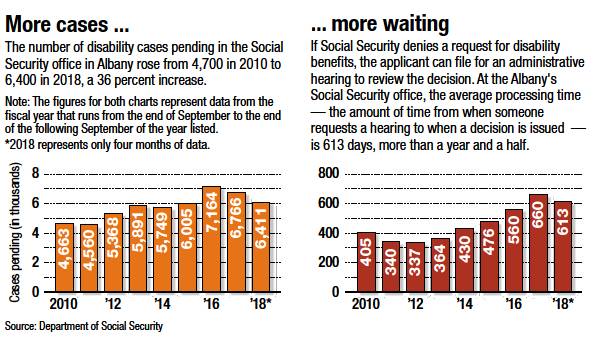

In 2013, the average time from the date someone requested a hearing until it was held in Albany was 12 months; by this January, the wait had stretched to 18 months. Across the state, federal data show, the average time from a hearing request to a decision being issued is 693 days and in Albany, where Lestingi will travel for a hearing, it’s 613 days. Offices in the Bronx, Manhattan, Queens and Buffalo make up four of the top 10 offices with the longest waits.

“Reducing the wait times for a hearing decision is of utmost importance” said John Shall-man, the SSA’s New York City-based spokesman. The agency received a record number of hearing requests for several years running mainly because of baby boomers aging and the recession, and the agency’s resources to manage claims did not keep pace with the uptick, he said. The agency is making progress and has reduced the number of people waiting on a hearing decision each month for 13 months straight, Shallman said.

Wanting to work

Arturo Rodriguez, a Dutchess County resident, has been waiting for a hearing since October 2016, several months after his initial claim was denied. Rodriguez said he loved working, whether he was driving a school bus or installing television cables, but started feeling intense pain in his back and legs. Three pulmonary embolisms forced him to start taking blood thinners, and he started missing work more often.

“My mind was telling me I could work but my body was saying I couldn’t,” he said. “The things you used to do in the past you can’t do anymore.”

If a judge denies benefits, a person can then turn to the Appeals Council, a group of judges, appeals officers and staff headquartered in Virginia. The council generally sides with the administrative law judge and this step can take from eight months to more than two years, Mendleson said.

That’s the final decision administratively, but unsuccessful applicants can still turn to the federal courts. Mendleson said that a lawsuit filed in a federal district court may take a year or two to resolve. But atthat stage, a plaintiff’s chances of winning are better, he said.

" How people live for so long without any income ... the vast majority are not bankers, doctors and lawyers. Once the paycheck stops, what do people do?”

— Ira Mendleson

In the meantime, people seeking benefits aren’t working.

“How people live for so long without any income ... the vast majority are not bankers, doctors and lawyers,” he said. “Once the paycheck stops, what do people do?”

A shortage of judges

Advocates and industry experts attribute the backlog to a combination of factors: inadequate funding, an insufficient number of judges and support staff and more applications to process. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive think tank, found that the SSA’s budget fell 11 percent between 2010 and 2017 when adjusted for inflation “just as the demands on SSA reached all-time highs as baby boomers reached their peak years for retirement and disability,” senior policy analyst Kathleen Romig wrote.

The roughly 1,650 judges handling Social Security cases in the United States — 14 sit in Albany — are inundated with applications and don’t have enough support staff to help, said Marilyn Zahm, president of the Association of Administrative Law Judges. The size of the files that judges and staff must go through has also ballooned as a result of changes to regulations on what documents people submit, said Zahm, a judge who hears disability cases in Buffalo. Many applications are 1,000 pages or more.

As difficult as it is for those waiting, the crisis situation also affects judges and their staff, she said. Some work longer hours, often on weekends and on unpaid time, to try to manage the caseload.

“We are the people on the front lines,” Zahm said. “We see the misery these wait times are causing people. ... We see them, and that affects us. The American public doesn’t deserve this.”

The backlog is “fundamentally a math issue,” said Jason Fichtner, former deputy commissioner of Social Security and now a senior research fellow at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center. The number of people applying for disability benefits has steadily risen over time, but it peaked during the recession: Between 2008 and 2009 the number of SSDI applications rose from 2.3 million to 2.8 million, according to federal data. As the economy recovered applications began declining, dropping to 2.1 million in 2017. But many of the claims filed during the recession are still working their way through the system, Fichtner said.

There’s also confusion about the differences between SSDI, SSI and other programs, leading people to apply for the wrong one. The SSA has a self-proclaimed strict definition of disability: “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s) which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”

Benefits “are not in any way easy to get,” Ekman said.

A program called Compassionate Allowance allows people with certain cancers, brain disorders and other conditions that clearly meet the requirements to have their claims processed more quickly. But other health issues can be harder to assess, especially during the first stage of the application process: A stranger with a stack of documents must decide whether another stranger is physically or mentally incapable of doing the work they did before and can’t adjust to other work. People can’t get benefits for apartial or short-term disability — another requirement some miss, Fichtner said.

“In some ways, we’ve created a system that requires people to prove that they’re actually worse off than they are,” he said.

When someone does get benefits, it’s not a financial windfall. The average payment is $1,171 per month, afigure that “helps people keep a roof over their head and food on the table, but it’s certainly not living high on the hog,” Ekman said.

Still, for those who have been waiting for so long, the benefits are worth waiting for.

On Feb. 5, about a month shy of two years since he applied for disability, the letter Lestingi had been waiting for finally arrived. In three months, he will travel to Albany to plead his case before an administrative law judge. It could be an end to the long wait.

Or it could yield just another denial. Lestingi isn’t getting his hopes up.

“I’m relieved, but it’s still not a yes,” Lestingi said. “We will just keep doing what we’re doing to get by.”

Rodriguez is waiting for a letter of his own while trying to manage his ailments. Some days he can’t get out of bed because the pain is so severe, and sitting or standing for long periods hurts.

The mental toll it takes is also difficult. One of the things he misses most about working is talking to co-workers and going to office Christmas parties. He spends most of his days at home. The inability to work saps his confidence.

“You feel like you’re worthless, like you can’t be depended on because you can’t provide for your family,” he said. “It’s a long wait, but the mental game is even worse.”

• miszler@timesunion. com • 518-454-5018 • @ madisoniszler

" We are the people on the front lines. We see the misery these wait times are causing people. ... We see them, and that affects us. The American public doesn’t deserve this.”

— Marilyn Zahm, president of the Association of

Administrative Law Judges