Coach passes on lessons of her predecessors

Elizabeth Mosier

has recently completed anovel, “Ghost Signs”

The first time I tossed a softball to my daughter, she ducked instead of raising her glove. I hadn’t seen that coming, but when you’re coaching a team of third graders, no play is too basic to break down.

I learned this first from my father, who signed me up for my school’s summer league when I was the same age. I went along because it seemed important to him.

On Saturdays, Dad usually worked a half-day at Empire Machinery, and came home to drink a beer and mow the lawn. But on those weekends leading up to tryouts, he taught me to hit cleanly off a handmade tee and field with a brand-new glove broken in with Kneatsfoot Oil. For this man who knew engines and earthmoving equipment, no malfunction — of courage, will, ability — wasn’t fixable with a few adjustments: Glove to the ground … Foot on the bag … Point your toe where you want to the ball to go … Knees bent, bat back, swing! Though my hands were too small to do more than shot-put the ball, Dad assured me, “When you grow, you’ll be more graceful.”

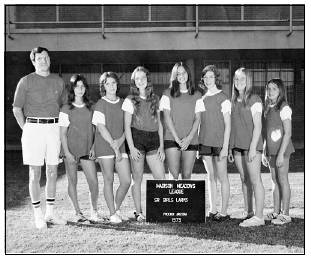

I loved those early-morning practices at the playground because I had my dad to myself. I still believed that he knew everything, so I was sure of my athletic destiny. And though I took up softball reluctantly, Iwent on to play for 10 more years — starting as a skinny Quail in a sun-faded purple jersey (our team named for a nervous, head-bobbing bird that rarely flies) and eventually becoming a shortstop and home-run hitter on the Cardinals, Robins, Larks, Falcons, Central High varsity, Phoenix city league, and the Bryn Mawr-Haverford Killer Penguins teams. For me, softball is a physical expression of grace.

I understood my daughter’s fear, but I wanted her to know the pleasures of the game. Not winning, necessarily, but whacking the ball over the outfield fence or scooping a grounder off the bounce. And so I became one of two female coaches in the land of dads: the Radnor-Wayne Little League.

My co-coach was a burly, good-humored roofer whose daughter would grow into an excellent multisport athlete (while mine, no surprise, became a theater geek). At our first practice, he stood by tolerantly, massaging sore muscles he’d earned at the gym, as I delivered a five-minute lecture on the best batting s t a n c e . Du r i n g games, he was strategic, putting my hyper-focused daughter in to pitch while I put her in right field to be fair. I shouted encouragement — even to the opposing team, girls I’d known since nursery school — while he offered specific, corrective criticism.

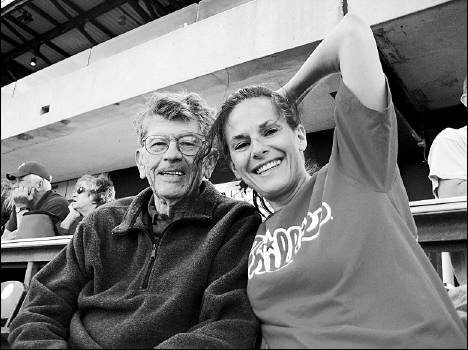

Among my coaching credentials are attending a Quaker women’s college and chairing gynocentric committees for the school PTO, so you might think my style had been shaped by consensus and collegiality. In fact, I was just echoing my dad. Even writing this essay I conjure his voice, absent and present since his death in May.

I’ve been thinking about fatherly guidance since talking to my old friend Mary, who attended the recent memorial for our beloved Larks coach, Robert Broomfield. As a kid, I must have known Coach Broomfield was presiding judge for the Superior Court of Arizona, but I couldn’t picture our patient, soft-spoken coach — Alyson’s dad — in a black robe pounding a gavel. Under his wise counsel, the Larks rose from last place to first in three years. I sought the same winning record when I asked him, years later, to officiate at my wedding as senior judge for the U.S. District Court of Arizona.

Mary conflated Judge Broom-field and my father, remembering

— perhaps because Dad played catch with us and attended every game, mortifyingly chanting “Hubba! Hubba!” from the sidelines — he’d assistant-coached our team. “Your dad recognized my athletic ability and tried to nurture that in me,” Mary said, her words like a ball hitting the bat’s sweet spot, sounding the satisfying crack of accuracy.

Mary was right. That was my dad. And how lucky we were to know Alyson’s dad, too.

Time doesn’t heal; grief isn’t linear; loss triggers loss. Some self-protective instincts must be unlearned before we can move on. That’s what practice is for, after all: to teach you to face a fast-pitched ball by watching the seams, to catch instead of dodge. When you grow, you’ll be more graceful, I tell myself when I feel like I can’t hold what’s in my hand, let alone let it go.

In this long season of losses, I’m grateful to all the coaches everywhere, who first oriented us to the rules of the game and pointed out the counterclockwise direction in which the bases must be run.

Contact Elizabeth Mosier at www.ElizabethMosier.com.

Í understood [her] fear, but I wanted her to know the pleasures of the game.