COMMENTARY

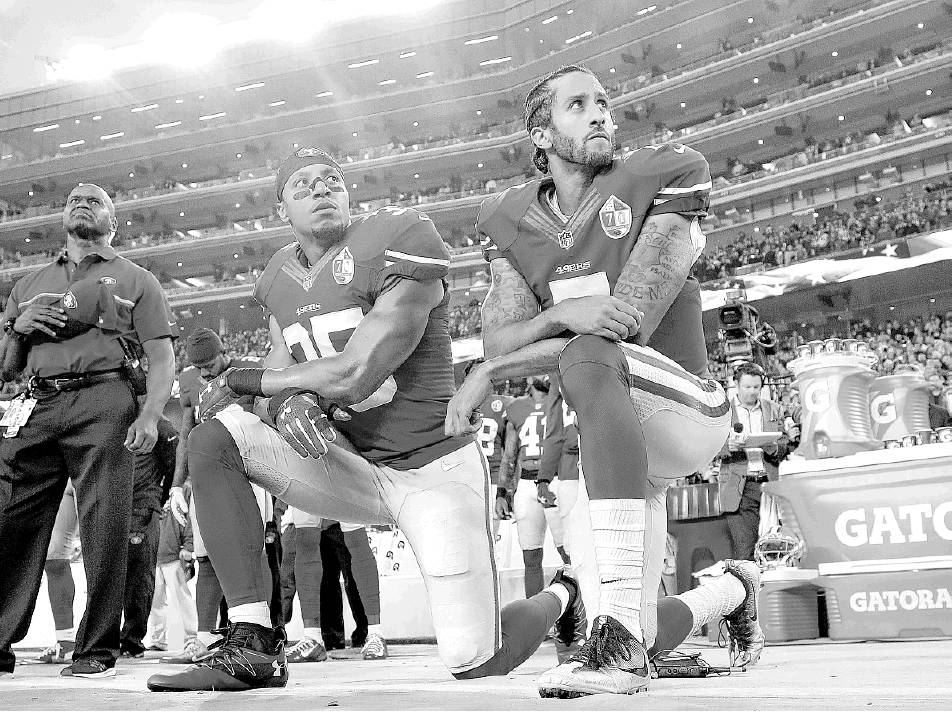

Kneeling protest steeped in religion

Demonstration is designed to show respect and humility

Last month, the National Football League announced that the league’s owners had come to the “unanimous” decision that “everyone should stand for the national anthem.” While players will be permitted to remain in the locker room in private protest, public displays will result in fines to the player’s team. The policy ostensibly aims to sidestep controversy that distracts from the game, damages ratings and reduces profit margins. But in actuality, the announcement provoked a firestorm.

The NFL Players Association expressed skepticism, promising to study the policy to see if it violated the collective bargaining agreement and insisting on kneeling players’ patriotism and good faith. Meanwhile, National Review cheered the new rules, comparing kneeling to flag-burning: “extreme” and “radical,” even if protected by the First Amendment. And of course the White House could not resist gloating, with Vice President Mike Pence tweeting that the NFL’s decision was a victory for the country and the Trump administration.

While pundits, politicians and the twitterverse debated the move’s consequences and constitutionality, few considered the longer history of kneeling in protest. Doing so makes clear the conscious and conscientious choice these players are making — as well as the unexpected religious origins of their protest.

In 1960, asmall group of Atlanta students conceived of what would become known as a kneel-in. At the time, most churches in the Deep South were rigidly segregated, with “closed door” policies barring black Americans from worshipping with white congregations. Seeing this as an affront to both racial justice and Christian brotherhood, these students were determined to integrate the city’s white congregations.

If permitted, they would enter and worship quietly; if rebuffed, they would kneel and pray in front of the church. “Most of us in the Atlanta student movement have increasingly felt the need to place this problem squarely on the hearts of white Christians,” one of the students explained, “feeling that every church, if it is truly Christian, by its very presence extends in the Savior’s name the unspoken invitation: ‘Whoever will, let him come.’ ”

Fanning out from Atlanta, these kneel-ins occurred hundreds of times, in cities as well as small towns. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee called kneel-ins “one of the next important phases of the student movement,” a variation on the sit-ins, wade-ins and stand-ins that were sweeping across the South.

But unlike sit-ins or marches, kneel-ins were distinct in their humble appeal to conscience and their posture of faith. Knees bent and heads bowed, the confrontation these kneelers provoked was certainly not physical — it was moral. By 1967, one journalist described the kneel-ins as “one of the most curious spectacles produced by the most profound domestic moral crisis of our time.”

The protesters who knelt before segregationist churches did not do so because they despised them. Quite the opposite: It was love that animated their protest. “I approached,” one of the Atlanta students said, “not as a demonstrator, but as a believer in an eternal, common Cause.” They were not agitating primarily for legal changes, but rather appealing to the Christian faith that they shared with clergy members and parishioners — beseeching them to see that segregation was un-Christian.

Nevertheless, the students peacefully kneeling before the doors of white churches confronted fierce opposition. Some defending the status quo doubled down on the right of individual congregations to enact segregationist policies. Many denounced kneel-ins as political posturing, a sullying of sacred spaces. Still others — perhaps in an effort to avoid the thorny moral questions being raised — evaded the spiritual appeal of kneel-ins by claiming that the protesters were acting insincerely. They were “just a bunch of agitators,” one Georgia man declared.

In the end, according to historian Carolyn Dupont, “the moral theater [that] played out on these church steps worked no conversion on their racial attitudes.” At least not right away. Over time, most churches abandoned official policies of racial exclusion, some with calm acquiescence to changing times and others only after strife and schism. But most congregations seem to have largely sidestepped the deeper theological and moral confrontation that the protesters hoped to provoke.

Almost 60years later, long after the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act and open-door policies, kneeling continues to ask questions of the conscience in its quiet way. Many NFL players choose to kneel not out of irreverence toward servicemen and women nor hatred of country, but out of love for America. As President Barack Obama once noted, dissent in the service of a better union can be “one of the truest expressions of patriotism.” Love for country, like love for the church, sometimes calls for kneeling.

And the kneeling itself matters. The NFL players’ decision to adopt that form of protest is significant. If the raised fist of black power connotes a certain defiance, kneeling seems to suggest apatient, almost religious protest — an appeal to our better angels.

Designed to show humility and respect, the act of kneeling beseeches. It is protest as supplication: When will the beloved community come? When will racial equality prevail? When will America fulfill its promise of liberty and justice for all? These are the deeper questions — for NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, for Pence and indeed for all Americans.

Ansley L. Quiros is an assistant professor of history at the University of North Alabama and the author of “God With Us: Lived Theology and the Freedom Struggle in Americus, Georgia, 1942-1976.”