Damage outside flood plain exposes flaws

‘We just need to start again,’ says professor about maps designating flood-risk areas

By David Hunn, Matt Dempsey and Mihir Zaveri

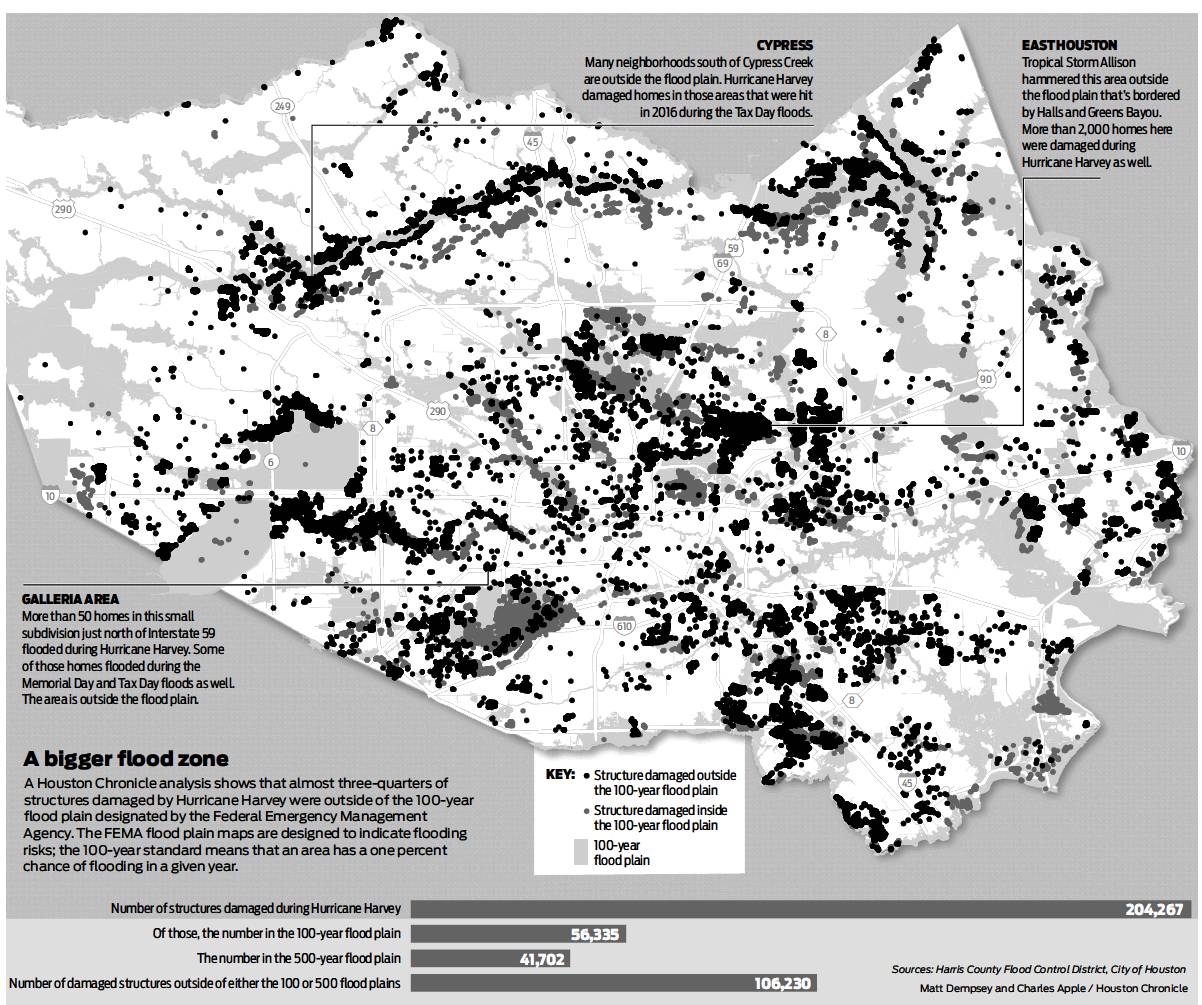

Hurricane Harvey damaged more than 204,000 homes and apartment buildings in Harris County, almost three-quarters of them outside the federally regulated 100-year flood plain, leaving tens of thousands of homeowners uninsured and unprepared.

The new details come from the most extensive disclosure of flood data yet released by city and county officials. The numbers follow a pattern: More than 55 percent of the homes damaged during the Tax Day storm in 2016 sat outside the flood plain, as did more than one-third of those during the Memorial Day floods in 2015.

The findings raise questions about local government plans to prevent flooding that focus on tightening building codes inside the flood plain. They also cast further doubt on the accuracy of the maps used to identify housing most in danger of flooding.

“We really need to throw out the whole thing and redo it, rethink it,” said Sam Brody, a Texas A&M University professor who has studied urban flooding extensively. “We just need to start again.”

Flood plain maps, designed by local governments and approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, guide key development decisions in flood-prone cities nationwide. The maps designate the highest-risk land as within the 100-year flood plain — land that would be underwater in a 100-year storm, or one that has a 1percent chance of occurring yearly.

Building inside that land triggers a litany of rules: New construction must be built above flood levels. Homeowners must have flood insurance for federally backed mortgages. Insurance rates inside the flood plain rise.

The 100-year flood plain has become the standard that the United States uses to judge flood risk.

Local officials are working to stem the floods they know will come. They’re talking about building a multibillion-gallon reservoir, digging underground tunnels and spending hundreds of millions of dollars to widen bayous.

They are focused on expanding tougher, more restrictive building rules into the 500-year flood plain, the next level above the 100-year, in which floods have a 0.2 percent chance of occurring in a year. But experts worry that any focus on flood plains may be too narrow.

The new data supports those concerns. Over half of the homes damaged by Harvey were outside all flood plain designations, meaning that such building rules, had they been in place during Harvey, still would have fallen short of protecting more than 100,000 Harris County homes.

Along Interstate 59 south of the Galleria, a few blocks in the Uptown neighborhood have flooded every year for the past three, yet they still aren’t considered part of the flood plain.

“I don’t care what they tell youffl” exclaimed resident Don Barrett, standing in his house, still stripped to its studs. “It’s in a flood plain.”

Barrett, 61, figured he’d live on Windswept Lane for the rest of his life. He grew up in the 1,600-square-foot ranch, raised his son there, and is caring for his 81-year-old mother there. But Harvey was his last flood. Barrett said he and his mother are selling.

“I’ve had enough,” he said. “We’re out of here.”

Hurricane season nears

Neighborhoods across Houston — from the high-rent Galleria to suburban Cypress to the streets of east Houston — sit outside the flood plain, but have flooded multiple times. Some homeowners tell of 5 feet of water during Tropical Storm Allison in 2001, followed by another 5 feet during Harvey. Others say they’ve flooded every year for three years.

Some have now paid the tens of thousands of dollars required to raise their houses. Many are moving, or planning to. Others are just stuck.

Betty Cuellar’s family ties kept her in east Houston for more than 50 years. Then Harvey hit, and her aunt, uncle and four nieces and nephews drowned trying to drive out of chest-deep water. Now her home on Talton Street, two blocks south of Halls Bayou, feels like a trap. She can’t afford to move her husband and five grandchildren; they barely scrape together $850 in monthly rent.

The least the government can do, she said, is tell people who live there what kind of risk they face.

“How many other lives could be lost next time?” said Cuellar, 52. “People need to know where they are living. I don’t even know what to say anymore.”

Down the street from Cuellar, Ruben and Gloria Arocha bought their 1,100-square-foot home in 1975 for about $15,500. They are outside the flood plain and didn’t think they qualified for flood insurance, so they paid out-of-pocket to rebuild after Allison hit, and hoped it wouldn’t happen again. Then Harvey sent 5 feet of water over their threshold.

“We lost everything,” said Ruben, 67, a former school district maintenance supervisor. The neighborhood is now half-empty, said Gloria, 66, a former school cafeteria worker.

If they can sell their home for enough money, they plan to leave.

“It’s going to be June soon,” Gloria said, her shoulders shaking, tears welling in her eyes. “Hurricane season is coming.”

New data, new rules

Harris County and its 30-plus municipalities spent months assessing how badly residents flooded during Harvey. Most sent teams to survey neighborhoods. Each municipality collected data slightly differently, the county said.

The city, for instance, compiled information from several sources: FEMA insurance claims, 911 calls, neighborhood drive-through assessments, flood plain structure inspections, and every single time a bulk-pickup trash truck opened its claw, the truck’s computer noted the location and the city tapped that spot as a home that flooded.

Officials have now begun to propose significant changes to building in the flood plain and protecting homes from future floods.

The county, for instance, has already extended building restrictions into the 500-year flood plain, and it is seeking to buy out 1,000 homes in the flood plain at the highest risk of flooding. It also has requested federal help to build a third flood water containment reservoir in the northwest, similar to Addicks and Barker dams.

Harris County Commissioners Court has even voted to study construction of a massive underground tunnel system to collect and transport storm water, first to the Ship Channel, and then to the Gulf.

The city plans to revisit citywide building codes in the coming months. But it has so far focused on the flood plain. Mayor Sylvester Turner has proposed rules requiring builders to raise new homes in the 100-year and 500-year flood plain 2 feet above the projected 500-year flood level — the storm with a 0.2 percent chance of occurring in any given year.

A recent city report found that more than 80 percent of the Houston homes in either flood plain would not have flooded during Harvey if they had been built to that standard.

But a focus on flood plains can neglect the thousands outside of them.

“It’s silly,” said Brody, the A&M professor, echoing other experts. “Over half of all the impact is outside these boundaries. That makes absolutely no sense to me.”

Roy Wright, aFEMA executive and director of the National Flood Insurance Program, said FEMA needs to better communicate flood risk and persuade more homeowners to buy flood insurance. But the issue isn’t the flood maps, he said. They’re updated on five-year cycles nationally and annually in some high-flood regions such as Harris County.

“I will stand by the product I have today,” Wright

-ible product, the best Ihave available.”

Still, Wright acknowledged that the science of flooding has evolved over the past two decades. Flood risk communication must, too, he said. “We need to improve,” he said.

Harris County Judge Ed Emmett, who leads the commissioners court, says the flood maps aren’t just troublesome, or misused. They’re wrong.

“We don’t know, for example, where all the tributaries are in west Harris County,” Emmett said Friday. “And we’ve got to know that. We’ve built on them over the years. Now people are living on them.”

“Clearly, we’ve done something wrong.”

In a statement released Saturday, Turner said the city council would take up the new development rules this week and acknowledged the inaccurate flood plain maps.

“It is essential that our county and federal partners update the floodplain maps so that the city and our residents may reference the maps for future planning and flood mitigation,” he said.

Maps change slowly

Harris County is studying now how water flows into the bayous as well as out of them. The current flood maps, said Matt Zeve, director of operations with the Harris County Flood Control District, only show how water leaves. The maps also don’t capture other problems with drainage systems — skinny storm sewers that choke runoff, narrow streets that can’t hold much water, and old gutters that don’t meet today’s regulations.

The flood control district is working on new maps that can better communicate flood risk, Zeve said. But they won’t be ready until 2022.

“It’s the big question,” said Jo Ann Howard, aformer FEMA executive who ran the national flood insurance program 20 years ago. “Is there a better way, with the technology we have, in delineating risk for the purpose of safety?”

Flooding in Houston will almost certainly get worse. Scientists say that climate change is already making storms more severe. Preliminary results from a key National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study indicate rainfall has increased markedly, but flood maps don’t yet reflect it. And in Houston, developers continue to build malls and subdivisions, paving over ranches, farms and prairie, open areas that once helped absorb rainwater.

But Jesse Blanton is not moving.

Last week, Blanton and his nephew, Jeremy Woodroffe, were putting flooring down on Blanton’s rebuilt pier-and-beam house in east Houston, north of Loop 610. The water during Harvey was up to mid-chest, said Blanton, 62. “It looked like the houses were sitting on a lake.”

Blanton and his wife bought the home for $72,000 in 2002, right after Allison. He previously lived down the street and knew the area flooded.

“Not in a flood plain? So they say,” Blanton said. “But every time it rains we get flooded the heck out. Last time, I put my wife on the roof. I put my daughter on the roof. I put four dogs on the roof.”

It has taken seven months to put their two-bed, two-bath bungalow back together. New walls. New ceiling. New everything. The work left Blanton, a retired truck driver, without his savings.

Still, this is home, he said. A bayou runs out back. “And I’ve got plans,” he said.

He’ll rebuild the old greenhouse, now just a shell of two-by-fours. He’ll turn the crumbling outbuilding into a beauty shop, for rent. He might raise a wooden gazebo in the yard. And he’ll keep watch over his fruit trees: a plum, apple, fig and pear.

He knows the water will come back. For some neighbors, it’s too much. But not for him.

“I’ve been 15 years on this piece of ground,” he said. “I’m too old to go anywhere now.” david.hunn@chron.com twitter.com/davidhunnmatt.dempsey@chron.com twitter.com/mizzousundevilmihir.zaveri@chron.com twitter.com/mihirzaveri